THE RUSSIAN WRITER Anton Chekhov was born in 1860, the son of a poor grocer. He studied medicine, supported himself and his family by writing, and eventually worked his way up to the profession of doctor. He travelled, lived five years on a country estate, and died in Yalta in 1904. He is today regarded as one of the finest writers of the short story. In short, he was a specimen of a Russian rarity, the upwardly-mobile peasant literary genius.

The above sketch is clearly skeletal, but it suggests already the themes with which Chekhov was concerned: rural life, the relation of the classes, and self-improvement through education. Most Chekhov stories involve something like the following. A Russian goes on a rural trip in harsh weather. He is brought by circumstance into the company of a differing social class. Someone brings out the samovar, or tea-urn, and conversation ensues, but the classes do not communicate. There is usually a long passage in which the protagonist dwells upon the absurdity of it all. This one, for example:

Why are there doctors and medical orderlies, he wondered, why are there merchants, clerks and peasants in this world? Why aren’t there just free men? The birds and beasts are free, aren’t they? So is Merik. They fear no one, they need no one. Now, whose idea was it – who says we have to get up in the morning, have a meal at midday and go to bed at night? That a doctor is senior to an orderly? That one must live in a room and love no one but one’s wife? Why shouldn’t things be the other way round – lunch at night and sleep by day? Oh, to leap on a horse, not asking whose it is, and race the wind down fields, woods and dales like some fiend out of hell! Oh, to make love to girls, to laugh at everyone!

There is a good deal to be said about this quotation and the attitudes it suggests. But before we come to the analysis, I should like to explain why I’ve chosen this particular passage. For I could as easily have produced a dozen other on the same theme, all of them making the same point. I chose this one because I have thought exactly these very thoughts. ‘Who decided we must eat breakfast in the morning? sleep at night? work from dawn to dusk for a wage? dedicate our lives to consumption? look forward to the weekend and retirement? etc. etc.’ One can hardly live in an organized society without feeling the subtle and not so subtle external compulsions that determine so much of her behaviour. Are we free? Most of the time we think so, but then come those moments when we know we are living according to a script. It interests me that those moments involve things like breakfast and sleep. After all, war is obviously absurd, but breakfast? Precisely what feels natural, precisely this is being questioned. Beneath the careful crafting of a Chekhov story, one discovers the question, Could the world be otherwise than it is?

The question Could the world be other than it is? tosses us into politics. Here we find what I shall call the skeptical turn of mind – that is, the calling of things into question. A writer whose characters wonder over the meaning of breakfast could hardly be expected to accept human arrangements at face value. Yet what did Chekhov think? He seems to disapprove of the abuses of the Russian class system, but what would he put in its place, if anything? That is the rub. On first reading Chekhov, I find a vague humanism and a pervasive skepticism. Life is absurd. Yes, the peasants are getting shafted, but look at what sort of folk they are! Stubborn, bigoted, suspicious, and above all, stupid. They cannot even perceive their self-interest. Chekhov is commonly portrayed, along with James Joyce, as an exemplary model of the disinterested and apolitical writer. If he is unwilling to accept flattering nonsense about the aristocracy, he is equally unwilling to romanticize, in the common manner of the social reformer, the common folk. The consensus is that he merely describes the world without rendering a judgement.

Is this correct? Consider ‘An Awkward Business,’ which examines an incident between a country doctor, Gregory Ovchinnikov, and a medical orderly, Michael Smirnovsky. Here, as elsewhere, Chekhov establishes a set of contrasts. The doctor is young, educated, and thoughtful. Furthermore, he is a professional with aspirations. Chekhov is careful to note Gregory’s “keen interest in ‘social problems,’” a phrase which seems to me deliberately fuzzy. For Gregory, in contrast to the aged, bumbling, alcoholic Michael, is profoundly at odds with something we would call the system, and yet he’s unable to put his discomfort into practical language. Gregory’s problem is this: he has punched Michael in the face for coming to work drunk. He knows this is unprofessional behaviour, and that he ought to be disciplined, and yet the norms of 19th-century Russian society make only one outcome possible. The ‘old boys’ will rally around Gregory, and as a consequence his behaviour will be pronounced just. Indeed, this is precisely what happens.

Regarding the workings of the system, Gregory comments on ‘the sheer, the crass stupidity of it all.’ Here we have the perspective of the radical, the would-be reformer who is interested in social problems. Gregory seems to me to have Chekhov’s sympathy, but the implicit lesson of the story is that, like it or not, the system works. That, after all, is its function – to keep things moving along. Michael himself understands this and begs the forgiveness of his assailant. It is only when the embarrassed doctor suggests instead a lawsuit against himself that things get complicated. The expedient course of action would be to observe social conventions and let the system do its work. Why drag impractical notions like ‘social problems’ into the matter? No answer is given for this question. The impractical notions are simply there, and as a result Chekhov’s fiction is much more complicated than I’ve made it appear. His characters are plagued by a concern with justice, but they’ve learned to get along in an unjust world. It’s worth noting that the passage quoted above (“Oh, to leap on a horse…”) ends with this: “It would be a good idea to burgle some rich man’s house at night, he reflected.” In other words, once we have decided that the status quo is so much cruel nonsense, which clearly it sometimes is, we may move in any direction. Those directions include murder, robbery, and all manner of violence. Having questioned the prevailing arrangements, Gregory learns what everyone else has known all along, that things flow most smoothly when they follow the established channels. The alternatives are, as the story’s title ironically indicates, awkward.

The Chekhov I’ve proposed thus far conforms to the conventional notion of him as a wry observer of human affairs. But this Chekhov is, I think, too much a quietist, too much a man who merely contemplates things as they are without believing one can make a difference. That Chekhov was no reformer I agree. And yet I’m not satisfied with the view I’ve advanced thus far, that he is a skeptic and nothing more. He makes observable commitments and characteristic choices. There are implicit answers to the question, Could the world be otherwise than it is? In short, there is more to be said about the world of Chekhov’s fiction.

We may note the following. Chekhov is more interested in rural Russia than he is in the cities. Whatever implicit views he has may be inferred from his fondness for the ‘backward regions.’ He is interested in peasants, but he consistently narrates his stories from the perspective of the gentleman, or, where gentlemen are lacking, figures of relative high status. The protagonists are sometimes disdainful of their social inferiors but sometimes are ‘anxious,’ which is to say they encounter the lower orders with a mixed emotion of fear and desire. In the latter case, the upper classes do not wish to be confused with the down-and-out, and yet deep down they believe that the down-and-out lead a fuller, richer, more ‘earthy’ existence than they themselves do. The result is that the lower classes assume a sinister but compelling aspect, as in this passage from ‘Thieves’:

‘Phew, that girl has spirit!’ Yergunov thought, sitting on the chest and observing the dance from there. ‘What fire! Nothing’s too good for her.’

He regretted being a medical orderly instead of an ordinary peasant. Why must he wear a coat and a watch-chain with a gilt key, and not a navy-blue shirt with a cord belt – in which case he, like Merik, could have sung boldly, danced, drunk and thrown both arms round Lyubka?

Yergunov is nearly seduced by Lyubka, and he is robbed by Merik, but the greatest danger these characters pose is the one suggested by the story’s ending, that Yergunov will betray himself and defect his class. And why not? The peasants are having a wonderful time of it, robbing and killing with apparent impunity. Here we get another glimpse, I think, of Chekhov’s ‘position’ on the question, Could things be otherwise in the world? Nowhere does Chekhov allow class defection to occur without at least the suggestion of dire consequence. One has a choice to be a peasant or a gentleman; beyond that there is mere anarchy. Furthermore, class mobility is properly a matter of sustained effort and self-transformation. His is the sensibility of a man who through his own effort has left behind poverty and achieved success, and who believes that the answer is for others to do likewise. In short, he is concerned with personal evolution, not social revolution.

This explains the features of his work, some of which I have already identified. There is no grand social-reform vision in Chekhov’s stories because he is interested in the individual. This interest informs the manner in which he both criticizes and affirms the system. The system dooms the occasional intelligent, gifted individual to be born a peasant; nonetheless, for most peasants, theirs is a proper and even necessary role. As Kuzmichov comments in ‘The Steppe,’ ‘The point is that if everyone becomes a scholar and gentleman there won’t be anyone to trade and sow crops. We all starve.’ It’s not clear to what degree Chekhov endorsed Alexander Arkhipovich’s claim (in ‘An Awkward Business’) that ‘It’s only among professional people and peasants – at the two poles of society, in other words – that one finds honest, sober, reliable workers nowadays,’ but isn’t it interesting that he chooses rural settings, precisely where he may best concentrate upon these two classes. My suspicion is that, like Kuzmichov, Chekhov accepts the practicality of the class system. Social revolution is regarded skeptically, while the system, though evidently flawed, is at least valued as a source of social stability. Those characters who do accomplish a sort of revolution, for instance the protagonist in ‘The Cobbler and the Devil,’ find the results disastrous. The cobbler sells his soul to the devil in exchange for riches, but because he has not risen to his position through his own efforts, but instead by a sort of trickery, he is unable to fill his social position credibly. Despite his riches, he is still at heart a cobbler. When he wakes to find the whole thing was a dream, he joyfully accepts his humble lot. He has learned it’s where he belongs.

The Chekhov I am inferring may today sound reactionary, but we should recall the sort of ideas which were about in the 1890s. Social Darwinism was in ascendance in America, Germany, and Russia – to cite only the most historically significant manifestations. One of Chekhov’s late stories, ‘The Duel,’ repudiates proto-fascist notions about the lower classes, i.e., that they are degenerate and must be sacrificed to the greater good. Chekhov had no kind feeling for this point of view. Here however we may introduce another characteristic of Chekhov’s fiction, that it is almost oblivious to the stirrings of what has come to be called Modernism. A rural setting allowed Chekhov to explore the Russian class system, but the exploration is devoid of what really matters, from a modern point of view. I am referring to the conditions of urban life, the urban proletariat, the aristocracy, and mass society. His fiction looks backward, or tries to ignore the march of history altogether. Considered in its historical context, Chekhov’s decision to write mostly about peasants and gentlemen is remarkable.

I should address the accusation that Chekhov cannot be judged by today’s standard. Modernism did not come along until after his death, so how can he be expected to have written about it? I believe this accusation is misplaced, because clearly Chekhov did see what was happening. He knew that something one of his characters calls the ‘in-betweeners’ was emerging between peasant and gentleman (likely a reference to the rural bourgeoisie, known also as Kulaks or miroyed), and he knew about conditions of life in the cities. The point is, these did not interest him as a writer. He must also have been aware of grievances against the tsar, of the ‘Land and Freedom’ movements, and of the growing state repression of reform efforts. Nonetheless, Russia in 1890, for Chekhov, is farm labour, violent weather, inns, and samovars. ‘Upper classes’ means country priests, doctors, and clerical workers: in other words, gentlemen who have been educated out of the peasant class. As I’ve remarked earlier, these are the only two classes of person you’ll find. Chekhov also gives us murderous criminals, madmen, and exiles, but these are people outside society. They serve as a foil to his chief interests. Nor does class as such seem to be his concern. The peasants complain of their lot, and their suffering is presented sympathetically, but with a suggestion that it is inevitable, given their ignorance. There is no hint of the political struggles that culminated in the 1917 Revolution – struggles, one should note, that had been going on for many decades. One encounters the odd peasant rant against ‘the rich,’ as in the story ‘New Villa’ for instance, but we are never encouraged to take these comments seriously. Class oppression does not seem to be the problem for Chekhov, who himself had shown you could move about in Russian society if you had talent and a bit of gumption.

I am tempted to say that Chekhov’s fiction is informed by something akin to ‘classical liberalism’ or ‘meritocracy,’ but neither term is quite appropriate. I do think nonetheless that the stories imply a rejection of social reform (especially revolution) and that they treat ‘social problems’ as a matter of the individual. The world is recognized as a cruel and harsh place, and the poor are shown to have it badly. But Chekhov suggests that nothing can be done for them which will alter the fact of their poverty; alas, there must forever be peasants. One cannot read ‘New Villa’ without getting this message rather clearly. If the odd, individual peasant has talent and education, he may become a professional. In any case, the system will sort things out and people will end up where they belong, either among the peasants or gentlemen. Note that some, like Chekhov’s cobbler, will belong at the bottom and will only be harmed by artificial arrangements that put them elsewhere. The end result of the system may be harsh – will probably be harsh – and you may not like it, but such is life. That is the apparent moral of many a Chekhov story. Chekhov believed in private philanthropy and the obligations of rank (he helped to organize famine relief), and his story ‘My Wife’ shows he found the gentry’s mere lipservice to these deplorable. But the fact of wealth and poverty does not seem to have bothered him, so long as everyone bore his social rank with dignity and treated others kindly. The people who flout this principle get Chekhov’s harshest treatment. One however should not mistake the harshness as the sentiment of a reformer. If I am correct, Chekhov’s fiction offers us a qualified and careful apology for the class system.

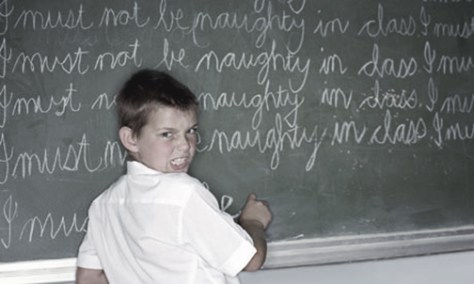

All of this no doubt sounds familiar. Something like the ideology I have been describing is emerging as the official political consensus in all the industrialized countries, including Canada. Already it is the dominant view in America. Put crudely, the beliefs are that social reform has been attempted and found misguided, most of the poor are the authors of their condition and aren’t helped by the state regardless, one’s social position is a matter of merit, the individual alone is responsible for his or her fate, and the best one can do is to alleviate suffering through private philanthropy. Along with the emphasis upon the individual we find renewed attention to education, crime, and the family. When the system is conceived as a mere collection of individuals, issues such as personal crime (as opposed to corporate crime), private education, and personal moral values will come to the surface. The behaviour of the individual will become the substance of reform. Class conflict, structural unemployment, systemic racism, and other such grand reformist catch-phrases will recede to the margins of public discourse. The system will be of little political concern. Reformation of the subject will be the political object. (June 1998)