Stories of Indigenous success can show the young what’s possible

WAYNE K. SPEAR | JULY 26, 2021 • CURRENT EVENTS

Among the world’s elite competitors are men and women of humble origin. The barriers to sport are many, especially for Indigenous people.

Still, stories of Indigenous sporting success are more plentiful than Canadians likely realize. One of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action is to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.

Not much is certain about the childhood of one of the world’s most versatile athletes.

Jim Thorpe of the Sac and Fox Nation was born in 1887, or maybe 1888, somewhere east of Oklahoma City. Described by Dwight D. Eisenhower as a “supremely endowed” athlete, Thorpe played in the MLB and the NHL and excelled at running, jumping, swimming, skating, basketball and other sports as well.

He attended the Haskell Institute at Lawrence, Kansas and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, established by a Civil War veteran named Richard Henry Pratt.

Pratt ran his school along military lines with a view of assimilating Indigenous people. He’s responsible for the phrase “Kill the Indian in the child, and save the man.”

The Carlisle school was studied by Nicholas Flood Davin, whose 1879 report to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald recommended it as a model for Canada.

At Carlisle, Thorpe prepared for the 1912 Stockholm Summer Olympics. He dominated, winning gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon.

The Onondaga marathoner Tom Longboat had, like Thorpe, a reputation for excelling without ever practicing. Journalists called him a “lazy Indian.”

He escaped a residential school (the Mohawk Institute, in Brantford, Ontario) to pursue running. His remarkable career began in 1905, and he was an almost-instant celebrity.

A poem titled “Tom Longboat’s Victory” memorializes his infamous 1909 race against Alfred Shrubb: “For days and weeks, twas talked about—the whole world echoed it; / A thousand papers flashed the news.”

The Tom Longboat Awards, established in 1951 to honour outstanding Indigenous athletes, attests to his inspiration of numerous Indigenous athletes.

At the time Longboat turned professional, several Indigenous athletes were competing in the Olympics: marathoner Fred Simpson in 1908, and in 1912 track and fielder Andrew Sockalexis.

The Hopi distance runner Lewis Tewanima, a teammate of Jim Thorpe at Carlisle, competed in both 1908 and 1912, winning a silver medal at Stockholm.

Thorpe returned to Carlisle to train but Longboat would never set foot again in the “Mush Hole,” as former students called the Mohawk Institute. He considered the place unfit even for a dog.

Sports played a complex role in the Indian residential schools. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples says that “in school, in chapel, at work, and even at play the children were to learn the Canadian way. Recreation was re-creation. Games and activities would not be the ‘boisterous and unorganized games’ of ‘savage’ youth.”

The school inspector J. Ansdell Macrae noted in 1888 that “a noticeable feature of [the Battleford Industrial School] is its games. They are all thoroughly and distinctly “white.” … From all their recreations Indianism is excluded.”

Football, cricket, hockey and baseball were meant to teach children self-discipline and conformity to the rules, “thus contributing to the process of moving the children along the path to civilization.”

Sport was also a respite. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, “many students stated that sports helped them make it through residential school.”

Andrew Amos was a provincial boxing champion. He was at the Kamloops school where the remains of 215 children were confirmed to lie in unmarked graves. He says that “it was through competitive sports … that we were able to cope and survive the daily routine of life at the residential school.”

The Oglala Lakota runner, Billy Mills, was orphaned at twelve. He chose to attend the Indian boarding school Haskell because his brother had gone there and he’d read good things about their sports programs. In 1964, Mills won an Olympic gold medal in the 10,000 meter run.

The brief hockey career of Fred Sasakamoose, of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, began at the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School, where he was forcefully placed after being taken from his parents in 1940.

Sasakamoose told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada that the school’s sports director, Father Georges Roussel, had a dream. “Freddie,” he said, “I’m going to work you hard, but if you work hard, you’re going to be successful.”

So it was. Sasakamoose was brought up from the juniors by the Chicago Blackhawks.

But years in a residential school had made him lonely and homesick. After only eleven games, his major league career ended. The Survivors Speak: A Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada quotes Sasakamoose as saying, “I didn’t want to be an athlete, I didn’t want to be a hockey player, I didn’t want to be anything. All I wanted was my parents.”

Fred Sasakamoose would join the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, established in 1998 to address the legacy of residential school abuses. Sport and recreation would be an important component of the healing programs funded by the AHF.

Racism has a long history in sport, and particularly in the Olympics.

The shambolic 1904 games in St. Louis were a celebration of imperialism and racial superiority, featuring a sideshow of “primitive” contests called Anthropology Days that included lacrosse and spear throwing.

At the 1976 Montreal Olympics closing ceremony, 250 non-Indigenous dancers entered the stadium costumed in feathers, buckskin and redface.

They performed a faux Indian tribal dance, based on a traditional Provençal farandole, to a composition called La Danse sauvage. Then they marched into the five Olympic rings, each with a tepee in the middle, despite the fact that Montreal is on longhouse territory thousands of kilometres from the tepee-using nations.

In 2015 there was scandal when Dsquared2, the company contracted to design Team Canada’s Rio Olympic clothing, launched a line of women’s apparel called Dsquaw. Stereotypes that had shaped the Olympics over a hundred years ago were again on display.

For the first time in its history, the Olympics in 2010 included Indigenous people as official partners. The Squamish and Lil’Wat First Nations incorporated the Four Host First Nations Society (FHFN) with the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh, and members of all four nations became involved in planning.

Canada’s history of colonialism and forcible assimilation has produced other barriers to sport — hopelessness, addiction, broken families, impoverishment, and isolation.

The more fortunate have the support they need to train and compete at an elite level.

Three times a week Montreal Canadiens goaltender Carey Price (of the Ulkatcho First Nation) was driven by his father to Williams Lake, 320 kilometres from home. Eventually Jerry Price bought a Piper Cherokee aircraft to cut their ten-hour commute.

The Inuvialuit cross-country skier Jesse Cockney competed at the Sochi 2014 Olympics, and at the 2011 Canada Winter Games he won three gold medals and one bronze. His father Angus relocated the family to Canmore, Alberta so Jesse could have access to the Canmore Nordic Centre and its training programs.

Carey and Jesse are the children of professional athletes. In his younger days, Angus Cockney was a cross-country skier. Jerry Price was a goaltender, drafted in 1978 by the Philadelphia Flyers.

Jonathan Cheechoo moved to Timmins, 300 kilometres from his home in Moose Factory, to develop his hockey skills. It was difficult to be so far from family, but he had a great deal of support.

Not every young Indigenous person is so fortunate.

Rilee ManyBears, a runner from Siksika Nation, had to overcome the death of his father, depression, drug abuse and attempted suicide to achieve success in competition.

Alwyn Morris, a 1984 Olympic gold medal winner in the 1,000-metre sprint kayak doubles, left his home community of Kahnawake and moved to Burnaby, BC. He trained at the canoe club and cared for his ailing grandfather. Morris was a Tom Longboat Award winner and, like Longboat, an outstanding Indigenous athlete who inspired many other Indigenous athletes.

One of them was Waneek Horn-Miller, a fellow gold medal winner (at the 1999 Pan American Games) from Kahnawake. Horn-Miller was 14 when the violence of the Oka Crisis occurred, in the summer of 1990. During the chaos of an altercation, a soldier stabbed her near the heart with a bayonet, but she survived.

In some cases, seeming barriers like isolation and remoteness turn out to be advantages.

According to Jim Thorpe’s New York Times obituary, “his favorite diversion was following his hunting dogs in the forest, which helped to develop his magnificent body.”

Indigenous cultures with long traditions of living on the land promoted strength and endurance.

Gwich’in and Métis cross-country skiers Sharon and Shirley Firth saw their Olympic success and their experiences trapping and hunting around Inuvik as connected.

The Firth sisters also benefited from the Territorial Experimental Ski Training, or TEST, program. Developed by an Oblate priest, Father Jean Marie Mouchet, TEST promoted skiing across the North at a time when the Canadian military was colonizing the Arctic, upending Indigenous lives.

Where family and community support systems are absent or insufficient, sport programs must fill the gaps. But there’s some distance to go, as the Canadian Olympic Committee admits.

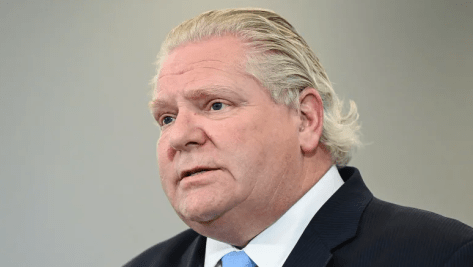

CEO, David Shoemaker, says the organization is focusing on promoting more Indigenous talent, both at the competitive and leadership levels.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called upon governments at all levels to ensure the development and growth of Indigenous athletes, continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, policies promoting physical activity, reduction of barriers to sports participation, and the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in programs and sporting activities — not only as competitors, but as planners.

Of the 676 Canada Sports Hall of Fame members, 12 are Indigenous. That’s under two percent, in a country where Indigenous people make up five percent of the population.

Stories of Indigenous success can inspire our youth and show them what is possible. Opportunities for athletic growth and development can help them reach the heights.

Three hundred athletes will represent Canada at this summer’s Olympics, but the COC doesn’t know how many are Indigenous. They don’t ask, but that’s something they are planning to change, and will need to change, if they are going to remove barriers.⌾

The worst thing that could happen would be for the Canadian public to forget this painful history

The worst thing that could happen would be for the Canadian public to forget this painful history

The Cariboo Indian Girls Pipe Band performed in Ottawa on July 1, 1965

The Cariboo Indian Girls Pipe Band performed in Ottawa on July 1, 1965