[This is an extract from my 1998 doctoral thesis. You can also read my thesis chapters on Eleanor Brass and James Tyman. The introductory, “Autopoetics,” chapter is here.]

Maria Campbell’s Half-Breed constitutes a Metis-centred history of the Metis and conceives history itself as an energising mythos in which both critiques of present social realities and radical hopes for the future subsist

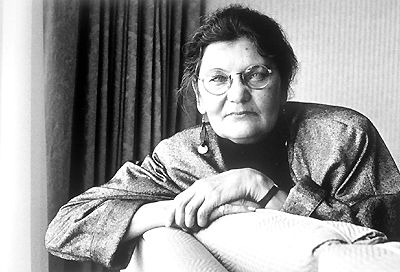

REMEMBERING WHO YOU ARE: The Synecdochic Self in Maria Campbell’s “Half-Breed”, by Maria Campbell (Halifax, Nova Scotia: Goodread Biographies, 1973).

“Surely history consists primarily in speaking and being answered, in crying and being heard. If that is true it means there can be no history in the empire because the cries are never heard and the speaking is never answered. ” -Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination.

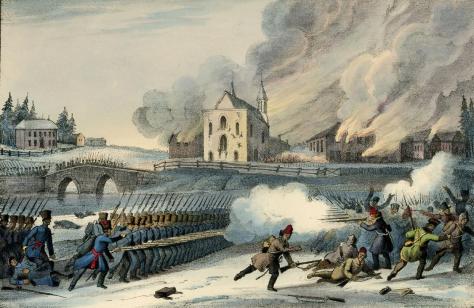

Maria Campbell’s 1973 autobiography Halfbreed constitutes a rebirth of the Native biographical genre, and hers is a text to which many who have followed refer. This work is striking for its breadth, beginning as it does with a summary narrative of Metis history, a history which frames the narrative of Campbell’s life. The autobiography begins, “In the 1860s, when Saskatchewan was part of what was then called the Northwest Territories and was a land free of towns, barbed-wire fences and farmhouses” (3). Campbell’s story is presented as a chapter, or rather 22 chapters, of Metis history beginning with the first white/native interactions and culminating in the 1869 Red River Rebellion and the 1884 battle at Batoche (following which Louis Riel was hanged, having been found guilty of high treason). Campbell summarises these and other key events, detailing the conditions within which they occurred and presenting the contemporary Metis grievances. Chapter One concludes with the outcomes of the 1884 battle, in the form of a list (6). Campbell establishes a perspective on this period of history (1869-1885) in a list recounting the events and ironically ending with the comment, “The history books say that the Halfbreeds were defeated at Batoche in 1884.” Such however is not the view either of Halfbreed or of Cheechum, a central figure of the narrative who “never surrendered at Batoche” (183). Halfbreed establishes Metis history as the contested ground of subjectivity and derives from its reconstitution of that history a synecdochic conception of the self. Halfbreed thus culminates in an expansive vision of solidarity which in many ways recapitulates the political struggles of Riel.

“Synecdochic self” is a phrase adopted by Arnold Krupat. According to the synecdochic model of selfhood, the individual is a part of the unfolding narrative of a people, and can thus be understood only in relation to the whole; “where narration of personal history is more nearly marked by the individual’s sense of himself in relation to collective social units and groupings, one might speak of a synecdochic sense of self” (Eakin 176). Here the collective social units and groupings under consideration are primarily the Metis people, but Halfbreed takes into consideration also class and gender groupings, and in the end a broad social community of those who seek justice. Indeed, at the heart of the autobiography’s “synecdochic vision” is a developing awareness of the complex inter-relations of gender, class, and race groupings which render solidarity both a logical and practical conclusion of the narrative:

I believe that one day, very soon, people will set aside their differences and come together as one. Maybe not because we love one another, but because we will need each other to survive. Then together we will fight our common enemies. (184)

In order then to understand more fully the workings of Campbell’s Halfbreed I shall attempt to analyse the constituents of this synecdochic vision, giving especial attention to the text’s dynamic representations of gender, class, Metis subjectivity, and history. As in the case in my investigations of Eleanor Brass and James Tyman, I hope to establish the structural-thematic principles according to which the text is organised and to describe the dictions and contradictions which articulate the discourse of the self. In short, I am attempting to elucidate particular instances of autopoetics, or self-making.

Cheechum serves both as the conveyor of the corporate past and the prophet of the future. Campbell’s synecdochic model of selfhood depends upon Cheechum for its substance, for Cheechum’s dual awareness of the crimes of the past and the promise of the future enables her to engage in a radical critique of the present. Maria’s analysis of the Metis condition is framed within Cheechum’s judgement that the state has “taught children to be ashamed” (159) and that governments were not made by the people; “it only looks like that from the outside, my girl” (159). Cheechum well understands the class economic interests which inform social reality, observing for example that war is “white business…between rich and greedy people who wanted power” (22). Cheechum notes further that the Catholic God “took more money from us than the Hudson’s Bay store,” an observation which integrates the religious institution into the project of cultural-economic imperialism (30). Maria’s experiences later confirm Cheechum’s class-based analysis:

I realize now that poor people, both white and Native, who are trapped within a certain kind of life, can never look to the business and political leaders of this country for help. Regardless of what they promise, they’ll never change things, because they are involved in and perpetuate in private the very things that they condemn in public. (137)

Significantly when the colonisation of Maria’s subjectivity reaches its zenith (in other words, when she is reduced to a “cold, rich, and unreal” sexual commodity and drug-addict) she finds herself in the presence of “politics and big business” (136). This convergence is perversely the fulfilment of Maria’s dream of material wealth as well as the disintegration of her “soul” (133) and even to a degree her body. Maria’s status as a commodity imposes upon her the requirement that she “forget about yesterday and tomorrow” (136), for the emptiness of her dream has become intolerable. The commodification of human relations, in which mere economic rationalism determines social reality, is exposed in all its ugliness. Maria performs her role as consort for a “wealthy and influential” unnamed partner. Her function is to “be damned beautiful and happy and entertaining” (137) in exchange for class-based privileges. In fulfilment of Cheechum’s sad prediction (134) Maria gets the “symbols of white ideals of success” she wants, exchanging for these symbols the substance of her “soul.” Cheechum, along with the Metis people, recedes from view as Maria becomes increasingly concerned not with the “tomorrow” of which Cheechum has spoken, but rather with the tomorrow of economic worries and the “next fix” (138).

The colonisation of Maria’s subjectivity is facilitated, if not driven, by the imposition of economic necessity. There is “no worse sin in this country than to be poor” (61), according to Maria. It is this sin of poverty that drives her to seek expiation in marriage, exile, and prostitution. The economic system of behaviour management complements and reinforces gender and class roles, interpolating Maria’s subjectivity into the contradictions of ideology. She subsists in the low- or non-paying gendered labour of the housewife and finds herself unable escape poverty. The contradictions of ideology inform her labour experiences as well as her subjectivity, for economic survival depends upon Maria’s ability to be the kind of women men like (97): “It made me feel that I might as well give up right then as there was no way I could ever be the combination of saint, angel, devil and lady that was required” (97). Maria’s work experiences consistently reproduce the contradictions of gender ideology. Gender ideology invariably domesticates her social and economic roles while introducing the notion of a threat to domestic stability. Thus, Maria’s employers rely upon her domestic skills while anticipating sexual indiscretions. Maria is a potential whore in the household whose presence necessarily elicits surveillance. Race ideology reinforces the notion of a whore-housewife, as demonstrated by an employer’s claim that Indians are “only good for two things – working and fucking.”(108). In short, the gender ideology which requires Maria to be a domestic labourer also renders her labour of dubious utility. As in other contexts, the accusation of “whore” is never far away.

First let us consider the matter of the writing of history. To write a Metis history is to practice radicalism (radix), for the Metis of the popular imagination is a creature whose essential characteristic is that he dwells outside history, history here understood as a people’s evolving self-realisation through purposeful agency. To write a Metis-centred history is thus to contradict officialdom’s most cherished rationalisation, that the Metis are not a people. The term “Metis” however properly refers to a distinct group, those whose origin can be traced back to the Red River in the early 1800s. These are the people, now located mainly in the prairie provinces and in the north, who joined together to fight the Hudson’s Bay Company and who in 1869 formed a government to negotiate their entry into the Canadian federation. Theirs is a unique culture with unique languages, among them patois and Michif (Purich 10-11). Campbell distinguishes “three main clans” of Metis in three settlements, and then contrasts the Metis to Indians, not only on cultural and linguistic grounds, but also on the grounds of character traits:

There was never much love lost between Indians and Halfbreeds. They were completely different from us – quiet when we were noisy, dignified even at dances and get-togethers. Indians were very passive – they would get angry at things done to them but would never fight back, whereas Halfbreeds were quick-tempered – quick to fight, but quick to forgive and forget (25).

The narrative is informed throughout by its implicit reference to the history leading up to and following from the Rebellion, a history which, as I have already suggested, serves as the mythic centre of Halfbreed.

Like the writing of history, the writing of an autobiography conveys phenomenal ownership of the productive means of one’s life-narrative, in contrast to the historical determinism which is an implicit (and at times explicit) theme of Halfbreed. In other words, autobiographical production appears to confirm the notion of the “self-authorising I” but does not and can not obliviate the material conditions of native lives, which are typically far from “self-authorised.” In this lies one of the many contradictions of “Indian autobiography” and hence Indian subjectivity. A subject-producing institution, autobiography is rooted both in liberal ideology’s notions of rational self-mastery as well as in the ideologies of class, gender, and race from which institutionally-mediated formulations of identity must borrow. This contradiction, of a self-mastered subjectivity and subjection, is furthermore subsumed in the dynamics of state-capitalism itself, which call forth active, autonomous, individualist “economic man” while constituting a complex class-based social order. One is constituted by ideology both as a subject and an agent, both as passive and active. Autobiography, as a culturally-mediated object, discloses the many ideological contradictions of liberal state-capitalism. A negotiation of the contradictions of state-capitalist ideology, whether consciously pursued or not, is thus necessary for the author of autobiographical narrative.

Each of the texts under discussion discloses (with varying degrees of self-consciousness) a negotiation of ideological contradictions. The challenge for analysis is to articulate coherently the particular features of the negotiation. I have claimed earlier that the contradictions of autobiographical narrative are rooted in the economic and political institutions designed to “solve the Indian problem” (see Introduction). These institutions are themselves historically rooted in the dynamics of state control, which constitute the material foundation both of social relations and of ideological constructs. The analysis of autobiography here undertaken involves a search for the textualised configurations of subjectivity according to the historical, cultural, economic and ideological substance of state subjects. Recall that particular incidences of autobiography and biography are ritualised recreations of the cultural myth of subjectivity, and that it is therefore with the performance of this “ritualised recreation” that we are concerned – with how the text operates rather than what it “means.” Under these conditions we may turn to Campbell’s text and to the contradictions inherent within its performance.

Campbell’s Halfbreed roots the autobiographical “I” in a corporate identity: the Metis people, but also as the narrative develops the collective social groupings of women and the poor. Historical narrative facilitates a mode of autopoetics which is at once critical and energising, a mode which situates the cultural and ideological contradictions of the self within a broader project of collective agency. Maria’s personal story is relational, posited among and extrapolated from the struggles, frustrations, and dreams of the oppressed. The reader is presented with two chapters of cultural history and genealogy before arriving at the phrase “I was born” (16). Structurally the autobiography implies that the “beginning” of the autobiography’s “I” precedes its explicit narrative introduction. The story of the “I” begins before the “I” is born (a point exploited to humorous effect in the autobiography parody Tristam Shandy.) By the time of Maria’s birth we have encountered not only the Riel Rebellion, but also the failed attempts of the Halfbreeds at farming, the conditions endured by the “Road Allowance People” (8), and descriptions of Saskatchewan life in the 1920s. At the centre of this corporate history is the role of the land in the unfolding story of Campbell’s ancestors, for the social, legal, political and cultural dynamics represented in her people’s history are literally grounded, rooted in the struggle to occupy and to live from the land. Campbell alludes to the land in an introduction, and notes that “like me the land had changed, my people were gone, and if I was to know peace I would have to search within myself. That is when I decided to write about my life” (2).

The notion of looking inside the self is illustrated on page 171, where Maria is given a painting “of a burnt-out forest, all black, bleak and dismal” with “little green shoots” representing hope. Land thematically integrates the political struggle over physical resources with the narrative struggle for the factors of self-production, an integration which literalises the apparent pathetic fallacy of the autobiography’s introduction. Land and history are the principal sites of struggle between state and Metis for the control of critical resources. This struggle informs Half-breed’s conceptions of Metis identity and discloses the ideological contradictions of the colonised self.

The text’s contradictions involve the ideological substance of the concept “Indian.” As the Welfare Office bureaucrat remarks on page 155, “I can’t see the difference – part Indian, all Indian. You’re all the same.” For him, Halfbreed, Metis, Indian, and presumably a score of other terms circulate interchangeably within a verbal economy of the Indian. While Campbell certainly knows the difference between Indians and Metis (differences which are legal, linguistic, cultural, and historical), this verbal economy informs her articulations of the self. The signified “Indian” is never far from the text’s multiple signifiers of Native identity, even in the case of illocutionary efforts to speak beyond or against the verbal economy of the Indian. The Metis is always-already an Indian, entailing the concept’s pejorative declinations. While the term “white” appears to be taken for granted as a proper and plainly descriptive signifier in Native autobiography, the terms Indian, Metis, and Native (to cite only three of many) are rife with ambiguities and negative connotations. The Native writer’s relation to the signifiers which speak her is an uncomfortable one, bound as the signifiers are by the ideological horizon of the signified.

Campbell construes her discomforting engagement with the signified as a love-hate relationship (103, 117). In these terms the autobiography thematises the bounding of its verbal economy. The power of the signified is acknowledged by Sophie, who according to Campbell comments that “she had let herself believe she was merely a ‘no good Halfbreed’” (103). Alex Vandal, the village joker, decides in what could be variously interpreted as an act of resistance or a capitulation to racial prejudice (or both) “to act retarded because the whites thought we were anyway.” Maria too, in a passage reminiscent of Edward Ahenakew’s Old Keyam (“I Do Not Care”) comments, “What’s the use? – people believed I was bad anyway, so I might as well give them real things to talk about” (129). The signified has precisely this force, as Cheechum’s comment, “They make you hate what you are,” suggests (103). The “proper” subject-positions of the Indian/Halfbreed are only too well-known, and being known they are at times self-consciously enacted by Native and Halfbreed agents. (James Tyman’s autobiography is a good example of just such self-conscious enactments, as I shall attempt to show.) Racism thus becomes literally a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Considerations of racism and identity are introduced into the narrative alongside the themes of imperialism and colonisation. Recalling a love of books from her childhood, Campbell writes of her fascination with the stories of Cleopatra which she had then known. Her imagination having been “stirred,” the juvenile Campbell enacts, with the help of her cousins, “plays” derived from the familiar stories:

In good weather my brothers and sisters and I gathered our cousins behind the house and organized plays. The house was our Roman Empire, the two pine trees were the gates of Rome. I was Julius Caesar and would be wrapped in a long sheet with a willow branch on my head. My brother Jamie was Mark Anthony, and shouts of “Hail Caesar!” would ring throughout out settlement. (14 sic)

One of the ironies of this Metis reconstitution of imperial Rome consists in the careful attention to racial representation in an otherwise naïve performance of roles. Young Maria wants to play Cleopatra but is instead cast as Julius Caesar, for she is “too black” and her hair is “like a nigger’s” (14). A “white-skinned, red-haired cousin” is instead pressed into the role, assuming her place aboard a raft, her slaves at her side. Cleopatra’s status (she clearly occupies the central place in this play) calls unequivocally for an Aryan representation. Race, class, and gender are each assigned their proper roles and places in this miniature rehearsal of historical imperialism’s social determinations. The Empire, in other words, arrogates to itself the exclusive right to constitute subjects according to its dominant interests. The word “nigger” suggests the virulent racism which subsists below the conscious awareness of the actors, and though the white neighbours perceive the irony of “Caesar, Rome and Cleopatra among Halfbreeds in the backwoods of northern Saskatchewan” (14) a greater irony may perhaps be the thematic appropriateness of this scene. The irony lies in the fact that matters of imperialism, colonisation, and racism may be abundantly clear in a representation of ancient Roman history while being indiscernible to the witnesses of the affairs of the modern and contemporary state. Imperialism nonetheless both produces and reproduces its conquests in the constitution of Indian subjects, an idea enacted not only within this scene but within the autobiography as a whole. Metis history and subjectivity are obliterated and in their place are put the White Man’s Indian.

The Cleopatra motif reappears in Chapter 22, perhaps the bleakest section of the narrative. Maria, institutionalised subsequent to her breakdown, revisits the world of make-believe:

They would be all right until a nurse or doctor came along, and then they would feign insanity. Sometimes they were moved to another ward, and eventually some received shock treatments. One attractive lady in her late forties had been there for over seven years. She believed she was Cleopatra, and spent hours sitting on a chesterfield. Sometimes one of us would feed her and pretend to be her slave.

Here play takes on a sinister aspect not at all like the play in which Maria has previously engaged. This Cleopatra is ironically described as an “attractive lady” (ironic because in the brutality and bleakness of her environment an attractive lady is incongruous), and the slaves at her side vividly depict the theme of power and powerlessness which is only suggested in the Cleopatra scene on page 14. The Alberta Hospital Cleopatra undercuts Maria’s earlier glamorous conception (“Oh, how I wanted to be Cleopatra”) and raises disturbing considerations of gender, class, and institutionalisation. An attractive lady would not likely find herself in such circumstances, though a woman of modest means like Maria may. In the female environment of the hospital powerlessness is graphically presented, the only “exception” being the mock pregnancies of a “fairly stout woman, with the most enormous belly” (163). I designate this an “exception” because there is an apparent and ironic appropriation of the female power of reproduction, an equivocal power, rooted as it is in patriarchal social and economic relations.

Awareness of patriarchal values shapes a number of Campbell’s reflections upon gender. Her father, we are told, is “disappointed” by the arrival of a daughter (16) and remarks disparagingly to his sons, “Dammit you boys! Maria can do it and she’s a girl!” (34). His conception of women is determined by a decent girl/whore dichotomy (111-112) which Campbell construes in the following terms:

On our way home Dad and I talked about babies, men, women and love. I asked him what kind of women men liked – I have to laugh now at his description. It made me feel that I might as well give up right then and there as there was no way I could ever be the combination of saint, angel, devil and lady that was required (97).

Campbell identifies the sexism of Native political organisations which “women were not encouraged to attend unless a secretary was needed” (182). She discerns in this attitude both general systemic determinants – what she calls “the system” – and the particular influence of missionaries who “had impressed upon us the feeling that women were a source of evil. This belief, combined with the ancient Indian recognition of the power of women, is still holding back the progress of our people today” (168). This account proposes an interesting case of ideological syncretism as well as a surprising manner in which ideologies can intersect and reinforce one another.

Representations of gender in Halfbreed comment variously upon gender roles and norms. Female beauty is a recurring motif of the narrative, whether the beauty of the Alberta Hospital Cleopatra or the beauty imposed upon the corpse of Maria’s mother and washed away by the horrified witnesses (78). Campbell notes the beauty which attends Lil’s prostitutes (137) as well as Darrel’s materialist sister, appropriately named “Bonny.” The description of her as “beautiful…and also very cold” (125) is a formula we meet in both instances, as well as in the description of the immigrants (27) and the transformed Maria, who we are told is “cold and unreal, rich and expensive” – and I presume beautiful in the manner expected of a prostitute (134). One insight to be drawn from this last episode is the relation of these depictions of beauty to agency and the self. The beauty of a prostitute, for example, is an instrumental value which serves economic necessity. Hence the intersection of beauty, money, and coldness, “cold” suggesting an absence of humanity. Indeed, in a world dominated by money relations all human interaction risks becoming predominantly instrumental in character:

I thought to myself, “Love! They all love you if they are on the gravy train. He can afford to love me. I made him good money.” I neither hated nor loved him. He was a means to an end, and I didn’t feel I owed him anything. (141)

We have already encountered Eleanor Brass’s comment upon the importance of money in the white man’s world (Brass 47). Maria’s conception of wealth and beauty involves at least in part a failure of logic, for these things begin as symbols of the good life but eventually become substitutes. In other words, the instrumental value becomes itself an end value, with disastrous results. Maria’s dream of wealth and beauty, innocent in itself, is co-opted by social relations which define the female subject as a commodity.

There are of course alternative models both of the self and of social relations. The commodified self rooted in instrumental social relations however is a subject position assumed by Maria in her dream to live in “a beautiful world full of beautiful people with no feelings of guilt or shame” (137). The dream of her materially-impoverished youth in this case is fulfilled only at the expense of agency and the self:

Dreams are so important in one’s life, yet when followed blindly they can lead to the disintegration of one’s soul. Take for example the driving ambition and dream of a little girl telling her Cheechum, “Someday my brothers and sisters will each have a toothbrush and they’ll brush their teeth every day and we’ll have a bowl of fruit on the table all the time…. Cheechum would look at her and see the toothbrushes, fruit and all those other symbols of white ideals of success and say sadly, “You’ll have them, my girl, you’ll have them.” (134)

These ideals of success, which are class-specific (Maria having associated them with wealth) as much as they are “white,” manifest themselves to Maria as a relation of the self to objective signifiers of status, as in the case of the business suit (67-68). “To own a suit and hat was a real status symbol,” Campbell writes, reflecting that in later years her awe is transformed into sorrow by the absurd pictures of men in ill-fitting clothes (68). Ironically the “holy” suits only underscore Metis poverty, for the pathetic attempt to look the part invariably fails. Toothbrushes and fruit further substantiate the theme of self-objectification, that is, of rendering the self an agent-less object of social relations. Cheechum “sadly” tells Maria she will have the “symbols of white ideals of success,” a prediction whose fulfilment clarifies Maria’s quest for her identity. Cheechum’s critique of the “white ideals” is implicit on page 98, where she says “Go out there and find what you want and take it, but always remember who you are and why you want it.” Cheechum here makes the distinction between material wealth as an instrumental value and an end value, and the word “remember” further suggests the critical function of memory in the constitution of the self. Maria’s failure is to render who you are equal to what you have, an understanding which abstracts the self from memory and history and posits it among object relations.

Prostitution fulfils the logic of the self-as-object, as commodity. Maria is taken to a “fashionable” dress shop and afterward to a beauty parlour. Having become the glamorous woman of her dreams, she is given an opportunity to contemplate the transformation:

When I was finally pushed in front of a mirror, I hardly recognized the woman staring back at me. She looked cold and unreal, rich and expensive. “Dear God,” I thought, “this is how I’ve always wanted to look, but do the women who look like this ever feel like I do inside?” (134)

The mirror image graphically imposes upon Maria the contradictions of her subject-position. She confronts herself as object – as simply another symbol, like a toothbrush or a bowl of fruit. The contradiction forces her to evaluate the conventional image of success which she has cultivated, for clearly inner does not correspond with outer. The contradiction of inner and outer initiates a critique of the material signifiers of success, a critique which will be evident in later sections of the text. At this point in the narrative, however, there is merely a recognition on Campbell’s part that the dream of success pursued thus far is empty. Campbell writes, “I lost something that afternoon. Something inside of me died” (134).

The death of one dream does not immediately bring about the birth of another. Structurally, chapter seventeen constitutes a negative space between the commodified subjectivity which has been the dominant (but not exclusive) concern of the early chapters and the synecdochic subject which shall dominate later. The term “negative” is employed because the subject-position adopted in chapter seventeen is “no self”; Maria recognises the perversity of a “self-as-object” model but finds the demands of agency insupportable:

Most of the girls at Lil’s used pills, and once I discovered them the world became a great deal more bearable. I took them like they were going out of style. They helped me to sleep, they kept me happy, and most of all, I could forget about yesterday and tomorrow. (136)

Forgetting is the means by which the self rooted in a historical narrative is negated. History, to borrow from James Joyce, is a nightmare from which Maria wishes to escape. Profoundly informed by history, Halfbreed conveys the horror of a history-less existence. Severed from an energising past and future (which the narrative derives from the story of Riel and the Metis people), the present is static and deathly. Campbell describes herself then as “numb,” (136) which is another way of saying, as she has earlier stated, that something inside of her died (134). What has “died” at this point is human agency. This death manifests itself not only in an absence of memories of the past and imaginings of the future but also in the absence of a critique of the present. The death of the Chinese girl, for instance, is met with a resolute attempt on Maria’s part to pull herself together lest she “fall apart and be finished” (135). Maria herself attempts suicide and ends up in a hospital among women whose “greatest fear was being released,” that is, of becoming agents actively involved in the mess of existence (163). Smoky speaks for them also when he expresses his efforts “to forget we exist” (174). Cheechum’s admonition, “always remember who you are,” is here appropriate, for the hospital scene suggests a link between the institutionally-coopted subject and forgetting. Cheechum herself suggests such a link when she claims that the state offers blankets but steals souls (159). The subject subjected to the state in this way is emptied of agency and ceases to be fully human.

Campbell first relates Cheechum’s story of the blanket during the restaurant scene. Two Indian boys are mocked by a group of “drunk and noisy” white men, who yell, “Watch it! The bow and arrows are coming” (158). Narrative details lead the reader to associate this scene with an earlier incident from Maria’s life. The older child stops, puts his arm around his younger brother and, “with his head up,” continues walking (159). The resemblance of this scene to the town scene of page 37 is clear. In both scenes, the Indians are objects of a white gaze, which imparts to them the shame Cheechum traces back to state apparatuses, church and school in particular. The very concept “Indian” issues implicitly from this white gaze, a gaze which the church, the school, the welfare system and the paternalistic state as a whole constitute in an institutionalised form. We have seen this for instance in Maria’s encounter with the welfare office, where she is stripped of dignity and pride and is called by the state to recognise herself as an “Indian” subject. As a reward for her subjection, she receives a small amount of money: a “blanket,” to use Cheechum’s term.

Cheechum’s insight discloses what might be termed the politics of identity. Halfbreed examines power in its manifestations as instruments which name, for as Cheechum understands, the dominant culture sustains its privileges by fashioning the world in its image. Against Halfbreed’s energising Riel mythos, the dominant ideology pits a cinematic farce (111), thereby discrediting the call for justice at the heart of Metis history. The cinema screen functions as a state apparatus, for it calls its Metis audience to a recognition of itself in the image. In this context, the political function of Halfbreed is clear. As Leigh Gilmore argues, in the “transformative process of naming” lies the allure of autobiography. An autobiography empowers the writing subject to speak, as opposed to being spoken for. Having been “spoken” by the ideology of the coloniser, Maria sees her destiny as determined by a choice between failure and assimilation. This choice rests on the assumption that to be Metis is to be poor and dirty, whereas success (in the form of toothbrushes and bowls of fruit) comes to those who become white. The only other “respectable” identity left to the Metis in the present order is a parodic one: the Calgary Stampede Indian, for example. The Indian is an anachronism; white history dictates that the present belongs entirely to the whites. Autobiography offers Campbell a recourse to the discursive production of an alternative reality, and enables her to reconstitute both Metis history and a synecdochic model of selfhood. Thus Halfbreed ends both with an affirmation of solidarity and the words “I no longer need my blanket to survive.”

Solidarity subsists in the common historical grounding of various subject-positions presented in Halfbreed. Metis and non-Metis poor, for example, share comparable experiences, while Metis women in their experiences of work have more in common with other women than with Metis men. The subject-positions of Metis, women, and the poor are represented in a narrative which grounds oppression and poverty in the history which has yielded Canada:

So began a miserable life of poverty which held no hope for the future. That generation of my people was completely beaten. Their fathers had failed during the Rebellion to make a dream come true; they failed as farmers; now there was nothing left. Their way of life was a part of Canada’s past and they saw no place in the world around them, for they believed they had nothing to offer. (8)

The Rebellion was, as the “official” account on page 6 suggests, the final impediment to the dream of a nation stretching “from sea to shining sea.” Those defeated at Batoche disappear as agents from this history. Poverty, which discloses their (non)relation to the prevailing modes of production, forecloses the future and hence renders dreaming futile. The marginalised share in common a present in which they see for themselves “no place in the world around them” as well as a past which is irrelevant and a future which is impossible. Human agency in such conditions becomes an intollerable burden, and a people forced to endure the burden end up “merely existing,” a phrase employed by Campbell in the Introduction. Mere existence is the antipode of historical existence, and Halfbreed implicitly attempts to reconstitute the latter within a narrative informed both by remembering and hope.

Memory and hope merge in the failed effort of the Rebellion, which Campbell recapitulates ironically. Following a disappointing encounter with the CCF, Campbell’s father becomes involved in Native politics, becoming a strong supporter of Jim Brady. This chapter is an ironic repetition, in miniature, of the disappointments following the defeat of Riel. The arrival of Jim Brady is attended by hope and excitement, both of which find their expression through Campbell’s father. Although Jim Brady is clearly the driving force of the political agenda, the narrative construes politics as domestic drama, casting the father in the role of hero. The Campbell family becomes a part of the Riel struggle, just as the meaning of Campbell’s individual life is itself synechdochically related to the corporate history of the opening chapters. The Riel mythos provides both a set of compelling symbols and an explanatory framework for the past, present, and future. In Riel, the terms of the struggle are articulated and the people find an energising narrative of origin and destiny. The domestic drama is therefore cast in the symbolic terms of the Riel mythos:

Daddy went to meetings all that year. He didn’t go trapping and so we were very poor. He was gone nearly all the time, and when he was home he would be very moody, either so happy that he was singing, or else very quiet. We all suffered these times with him. It seemed the Mounties and wardens were always at our house now. We were treated badly at school, even our teacher would make jokes about Dad, like, “Saskatchewan has a new Riel. Campbells have quit poaching to take up the new rebellion.” (74)

The irony of the invocation of Riel is clear enough. It is intended by the whites as a form of derision. Furthermore, it is true that neither the victories nor the defeats of Campbell’s father can claim the historical significance that the life of Riel can claim. Structurally, however, the invocation is a serious one, for in this chapter ( Chapter Eight) Campbell first becomes politically-conscious, and the perennial struggles of the Metis are first given expression:

Jim [Brady] said almost word for word what I have heard our leaders discuss today: the poverty, the death of trapping as our livelihood, the education of our children, the loss of land, and the attitude of both governments towards out plight. He talked about a strong united voice that would demand justice for our people – an organization that government couldn’t ignore. He said many people were poor, not just us, and maybe someday we could put all our differences aside and walk together and build a better country for all our children. (73)

The narrative is simultaneously mindful of past, present and future. The conditions of the past are linked to those of the present, and the subjunctive mood (“maybe someday we could”) projects the narrative into the future. Here the point being advanced is not merely that history is presented as repeating itself, which is apparent enough. Rather, a particular relation of structure and meaning is proposed. Through repetition, events take on their full significance. This relation takes us to a central implicit concern of the book, historical determinism. The repetitions that make the narrative meaningful also constitute a central problem for Maria: are her people doomed to repeat history? Again, we may think in this context of James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, for whom history is a nightmare to be escaped. Dedalus’s decision to “forge in the smithy of his soul the uncreated conscience of his race” proposes the transformation of personal and collective history in an act of literary re-creation. Campbell’s task is comparable: “Like me the land had changed, my people were gone, and if I was to know peace I would have to search within myself. That is when I decided to write about my life”(2).

Further observations could be made in relation to Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, particularly regarding the significance of imperialism both to Irish history and to Stephen Dedalus’s project of self-creation. Dedalus speaks of his alienation from the English language (182) and from the Christian religion (241), both of which he correctly views as imperial impositions, and rejects the offers of state institutions (principally the church) to affiliate himself with the empire through allegiance to its symbols and narratives. Dedalus’s assertion of non serviam [“I will not serve”] manifests itself in the “silence, exile and cunning” (238) whose mythic representation is Odysseus. It is especially fitting in this context that among Odysseus’s epithets are the terms metis (“cunning”) and polymetis (resourceful); clearly also exile is a central element not only of Campbell’s autobiography, but of the life of Riel himself (4). The suggestion here being made is not that Campbell is by virtue of a fortuitous pun an “Odyssean” author, whatever such an assertion may mean; rather, this brief interpolation of Joyce’s work is intended to suggest ways in which both autobiographical narratives (or in the case of the Künstlerroman, pseudo-autobiographical narrative) provoke a consideration of the constitution of subjects and subjectivities. Cunning is a practical necessity if the state production of subject-positions is to be challenged (For a discussion of Joyce and imperialism, see Vincent J. Cheng, Joyce, race, and empire. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997.) Halfbreed presents the multifarious state apparatuses involved in the production and reproduction of Indian subjects while constituting the terms of its self-determination of subject-positions, that is, historical agency.

One apparatus considered is the motion picture. The representation of history in a movie recalled by Campbell effects a successful appelation of subjects. The Metis apparently consent to the appropriation of their history and, in so doing, forego the opportunity to remember who they are, the task of historical agents:

One show I remember was about the Northwest Rebellion. People came from miles around and the theatre was packed. They were sitting in the aisles and on the floor. Riel and Dumont were our heroes. The movie was a comedy and it was awful: the Halfbreeds were made to look like such fools that it left you wondering how they ever organized a rebellion.

Here the very notion of a rebellion (which may raise the troubling question Why did people rebel?) is obliviated and replaced by a depoliticised comic vision of the Metis, complete with a “filthy and gross” Dumont and a Riel who is a “real lunatic who believed he was god” (111). History, with its troubling themes of imperialism and injustice, is displaced by triumphalism and the gratifying resolutions of comedy. The followers of Riel are appropriated to the prevailing cultural symbols of the day, emerging from this version of the Rebellion as “‘three stooges’ types” devoid of serious interest. Not surprisingly, the representatives of the state, in particular the NWMP, are recreated as heroic. Campbell notes the “hysterical laughter” of the Halfbreeds, who apparently are unaware that an ideological assault is underway. Cheechum however walks out in disgust.

The ideological assault on the Metis, and its concomitant production of subject-positions, manifests itself in a number of conventional assumptions. On page 8 we find the ethnocentric and essentialist notion advanced also by Eleanor Brass that Metis “just did not have the kind of thing inside them that makes farmers,” an assertion contradicted by the example of her father. This ontological assertion is particularly striking coming as it does after a lengthy materialist accounting of the barriers faced by the would-be Native and Metis farmer:

Due to the depression and shortage of fur there was no money to buy the implements to break the land. A few families could have scraped up the money to hire outside help but no one would risk expensive equipment on a land so covered with rocks and muskeg. Some tried with horse and plough but were defeated in the end. Fearless men who could brave sub-zero weather and all the dangers associated with living in the bush gave up, frustrated and discouraged (8).

I considered earlier the self-interest invested by whites in the notion that Indians were incapable of cultivating the land, a notion that Sarah Carter has argued to be false. Donald Purich furthermore has analysed the diverse legal and economic arrangements which rigged the system of property distribution in favour of white settlers and speculators, virtually guaranteeing that Indian and Metis farmers would be unable to take possession of the land. The result of government policies was that most of the land given to the Metis ended up in the possession of eastern speculators, whose predation was tolerated by the state, if not actively assisted. Campbell acknowledges the consistency of government efforts to undermine Metis organisation, but underestimates the role of the government policy in the expropriation of Metis land, relying instead on a ready cultural explanation.

The “failure” of the Metis is construed as a historical failure, part of the inevitable if poignant displacement of barbarism by civilisation. The Metis, in other words, failed to meet the challenge of history. Thus the Metis way of life is conceived to be “a part of Canada’s past,” an inference whose complement is (as I have suggested) the triumphalism of the empire. Campbell notes “there are some who even after a hundred years continue to struggle for equality and justice for their people,” a statement which recasts history in differing terms. History thus conceived is the product of human effort and inescapably subject to a moral accounting. The “white” version of history apportions only dehistoricised and static subject-positions to the Metis; only as commodity does the Indian serve a legitimate function. Business is “good in Calgary for Indians,” Marion notes (155), for the commodified Indian reproduces an ideological discourse which regards the Indian as a historical (that is dead) artefact. The Indian-as-antique manifests itself in the “gaudy feather and costumes” which Campbell equates with the “welfare coat” put on to get government money. In both cases it is a white man’s Indian devoid of humanity and historical agency, the same Indian who appears on the movie screen at page 111. Campbell deduces the source of her personal shame from these representations and from the subject-positions imposed upon her by political, economic, and cultural institutions.

Guilt and shame are emotions that Metis and Indians alike have acquired as a result of colonisation. These are a feature of the Indian subject. “Indianness” has been defined by the dominant (white) culture at the same time that Native and Metis traditions have been weakened or even supplanted; the result is that as the material conditions of Native people have been destroyed, the destroyers have rationalised the matter by redefining the Indian subject, paradoxically, as the agent of his own undoing. Such is the case in the official judgements regarding the Indian as a farmer, which tended to render as just the usurpation of land by whites. Campbell depicts the power inherent in this relationship, of coloniser and colonised, in a representation of what may be termed the anthropological gaze:

[The Metis] were happy and proud until we drove into town, then everyone became quiet and looked different. The men walked in front, looking straight ahead, their wives behind, and, I can never forget this, they had their heads down and never looked up. We kids trailed behind with our grannies in much the same manner. (37)

The transition from “happy and proud” to shameful suggests the implicit function of the “white gaze” (recall that Brass uses the term gaze in her depiction of the trip into town). The gaze interpolates the Indian subject, and in this instance even the children respond with the “proper” subject-position. The encounter of the white townspeople and the Metis discloses the intersubjectivity at the base of this shame-filled Indian subject; even Maria’s dream of escaping the shame of poverty is a mere reciprocation of the gaze. She respects (respectare) the “symbols of white ideals of success” (134) and in so doing recognizes herself as the Metis subject of the gaze. The response depicted on page 37 is elicited by the encounter of Maria and the Welfare agent, for whom Campbell acts “timid and ignorant” as she’s been instructed to do by Marion (157). This suggests that the welfare department, and presumably other state apparatuses, institutionalise the gaze, that is, the power of interpolating subjects. Notably an Indian child frustrates what may be construed as an interpolation on page 158 (“Watch it! The bow and arrows are coming”), walking “with his head up.” Cheechum already has exhorted Maria always to do the same (37), an exhortation which challenges directly interpolative strategies and the power inherent within them.

Poverty and the institutional arrangements deployed in its management are mediated by subjects, which is another manner of articulating the point that the ideologies of the welfare state constitute subjects for welfare state apparatuses. The Poor as such is an abstraction, rationalised in the fictive subject-positions where the state renders poverty subject to its own institutional and instrumental logics. This mediation-function of the subject is indeed what we encounter on pages 36-37:

I went to the [Welfare] office in a ten-year-old threadbare red coat, with old boots and a scarf. I looked like a Whitefish Lake squaw, and that’s exactly what the social worker thought. He insisted that I go to the Department of Indian Affairs, and when I said I was not a Treaty Indian but a Halfbreed, he said if that was the case I was eligible, but added, “I can’t see the difference – part Indian, all Indian. You’re all the same.” (155)

Maria has been instructed by a friend to perform for the Welfare agency: “Act ignorant, timid and grateful” (155). Here performance designates the simulation of a specific subject-position appropriate to the ideological assumptions of the welfare office worker, assumptions clearly articulated in this passage. Indians and Metis are “all the same” insofar as they together are interpolated by welfare-state apparatuses. The simulation of poverty involves a concomitant simulation of ignorance and timidity, what one may term following Cheechum the “blanketed subject” for which the state stands ready, arms filled with more blankets. Maria’s request for assistance is co-opted by the state and thus becomes an institutional encounter where agency is undermined and a passive subject constituted. Identity is objectified and reified in order to satisfy bureaucratic ends. The bureaucratic demands of the state furthermore resemble the economic demands of capitalism. As Maria notes, “To me [dancing in the Calgary Stampede] was the same as putting on a welfare coat to get government money” (156). In either case, she become merely “a white man’s Indian,” a subject amenable to institutional expedience.

The pervasiveness of institutions is a striking feature of Native autobiographies, especially those autobiographies written since World War II. In text after text, the protagonists are taken captive by one institution after another; relief agencies, welfare offices, prisons, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, psychiatric hospitals, and countless other entities make regular appearances. An Indian autobiography is, whatever else it may be, a reflection upon the multiple and contradictory modes of production of subjects in the paternalistic state of modern and contemporary times. Cheechum, as we have seen, puts the matter this way:

…when the government gives you something, they take all that you have in return – your pride, your dignity, all the things that make you a living soul. When they are sure they have everything, they give you a blanket to cover your shame. (159)

Cheechum includes in the category “government” the churches and schools, recognising their subject-producing function as state apparatuses. Significantly Cheechum emphasises the negative character of their operations; what they may impart (Christian religion, literacy, etc.) is apparently less important to Cheechum than what they negate – “all the things that make you a living soul.” The two, giving and taking, are regardless complementary, for the exchange constitutes an agent-less, soul-less subject. This is one of the lessons of Maria’s experience. Cheechum here describes not only the schools and the churches, but the tactics of treaty negotiations by means of which the Canadian government asserted its control. The treaty negotiations proposed an institutionalised rationalisation of imperialism, offering to Native peoples the opportunity to become subjects, on the Empire’s terms. Doubtless the offers of blankets were seen for what they were and met appropriate responses. In any case Cheechum’s characterisation of giving and taking succinctly captures the subtle (and at times not so subtle) operations of institutionalised encounters, where the state bids for subjects and the agent risks her soul.

The narrative’s contradictions, between individual and institution and self and other, are manifested both in the mirror scene (134) and the welfare-office exchange. In the former scene Maria regards the subject she has wanted to become and in the latter she becomes the subject she has wanted to avoid. Both subject-positions alienate Maria from “the things that make her a living soul,” principal among them being history and a synecdochic relation to others. The autobiography, in keeping with the narrative convention of closure, ends with a synechdochic vision (“I believe that one day, very soon, people will set aside their differences and come together as one” [184]); Cambell’s personal story is a part for the whole, and both together are an effort of “brothers and sisters all over the country” who seek together to throw away their blankets, and in so doing to ensure that “the whole world would change” (159). This is not a claim that the text resolves all conflicts and contradictions. Campbell, having derived from history a synechdochic understanding of her personal struggle, projects the struggle into an unspecified future: “one day, very soon, people will set aside their differences and come together as one.” Maria’s searching, loneliness, and pain are over because she has been restored to her brothers and sisters, but for Native people change will come only when together they fight their common enemies. This hopeful denouement is rooted in Metis history, particularly in the history of resistance and rebellion and in the refusal to surrender associated with Cheechum (183). Maria emerges from her “numbness” to find solidarity among “people like herself” (167), a reminder that it is not only Halfbreeds who have reasons to do so but, as in the days of Riel, “white settlers and Indians as well” (4). In short, while the synecodochic vision of Halfbreed’s closing pages extends to all peoples, it is nonetheless a vision which is profoundly Metis, derived from the promise of the Riel-centred Metis mythos by which Halfbreed is informed.

Campbell prefaces the introduction of her people with the words, “The history books say that the Halfbreeds were defeated at Batoche in 1884” (6). Following this is a list of events which constitutes the orthodox, white version of Metis history. This is the history which the white history books have spoken into existence: it is a history ending in defeat and death. Maria, however, says that “My Cheechum never surrendered at Batoche: she only accepted what she considered an honourable truce” (184). These two statements occupy the beginning and end of the narrative, and stand in opposition to one another. History as it is presented in the opening pages is “objective” and cast in the tragic mode. It looks dispassionately at the facts of the matter, which are beyond dispute, and finds poignant the inevitable deaths, which were in any case necessary to produce the present order. Halfbreed, on the other hand, articulates an alternative understanding of Batoche and its aftermath. It is an instance of constitutive rhetoric which, by its very existence, refutes the textbook proposition that the Metis were defeated in 1884, and thereafter disappeared as historical agents. Halfbreed constitutes a Metis-centred history of the Metis and conceives “history” itself as an energising mythos in which both critiques of present social realities and radical hopes for the future subsist.

My Fall 2014 book “Residential Schools, With the Words and Images of Survivors, A National History,” is available from Goodminds. Order by phone, toll-free 1-877-862-8483.