We don’t need, and we don’t want, a devil’s advocate to set us right about the value of Indigenous lives

✎ Wayne K. Spear | February 11, 2018 • Politics

I CAN’T IMAGINE ANYTHING worse than losing a child.

Now consider, for just a moment, how weak that sentence is. A cliché, wrapped around a euphemism, squatting on a conjecture. I don’t want to imagine the death of my son, or even to write the words, and I definitely don’t want to know what it’s like. Grant me the bliss of ignorance, now and forever.

The trial of Gerald Stanley is about the death of a son, about pain that requires no explanation, about the worst of all possible nightmares come true. If Mr. Stanley were sitting in a cell at this moment, the family of Colten Boushie would be mourning a loss all the same. For those who knew and loved Colten, there is today an expansive, terrible hole the universe will never fill. Every parent across Canada can sympathize with this, and so too everyone who has lost a brother or sister. Some things are universal.

But some aren’t in Canada, and the trial of Gerald Stanley is about this too. When the acquittal arrived, I was shocked but not surprised, like Indigenous people everywhere. I felt a sickening, heavy weight come down on me. I was angry and sad, outraged and hopeless. I wanted to kick something over. Instead, I went to bed, thinking it best to check out for a while.

My show the next day was about Indigenous identity, and how we’re all different from one another. I couldn’t have arranged worse timing for this topic. Yes, we are all unique, but in the hours and days after the judgement of innocence was announced, we felt the same emotions and expressed ourselves in a shared language of pain. Indigenous people experienced the Stanley trial the same way because our lives have been shaped by common experiences. We know instinctively that other Indigenous people get it, without anyone having to explain a single thing.

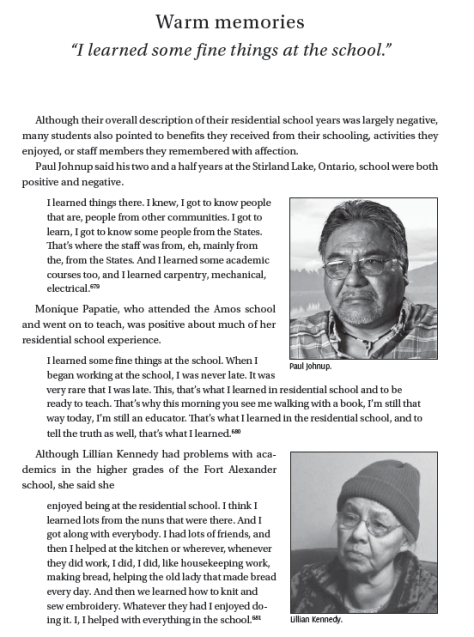

At the Toronto #JusticeforColten gathering, a speaker said she was exhausted by reconciliation. Aren’t we all. At times like this we’re expected to go on television or to write moving newspaper articles explaining ourselves to Canada. Everything we have lived and known is fodder for debate: the suffering of Indian residential school survivors, the legitimacy of our expressions of pain, the continued existence of our communities. We are told that our past is something to get over, and that our aspirations for the future are impractical. As for our present, we should show more gratitude and get on with assimilating.

When I was twenty-four, the Oka confrontation taught my generation of Haudenosaunee that our lives were of less value and importance to Canada than golf. We were forever changed by the Summer of 1990. Twenty-eight years later, our young people are living their Oka, by which I mean they are having their place in the Canadian scheme of things underscored and re-affirmed. The message is clear: it’s okay and even necessary to shoot an Indigenous person over a quad, because a quad is a valuable piece of property.

Ah, but what about the other side? Balance and fairness. The devil’s advocates and the debate?

Some things are universal, like the grief of a bereft parent. Canadians should at least be capable of expressing sorrow over this without having it explained to them. Unfortunately, Indigenous people are forever expected to educate the country and to give an account of ourselves, over and over and over again, as if Canada would be moved by our pain to change its direction. We’re exhausted, and we’re in no mood for explaining ourselves right now, and after this week we may never be again.