THE PHRASE “Indian Residential School System” refers to a historical church-state partnership formalized by the Government of Canada in 1892 with an Order-in- Council. Long before the late nineteenth century, many features of this system could be discerned. In the early days of Christian missionary work on the North American continent, beginning around 1600, religious orders established orphanages and schools for Indian children. These initiatives abroad were supported at home by private charitable donations known as subscriptions, and the work of securing the next year’s missionary funding drew the pious again and again back to the salons of high society.

From roughly 1500 to 1800, Europeans and aboriginal peoples regarded one another as distinct nations — in war as allies or foes, in peacetime as trading partners. Soon economic opportunity drew settler populations, and the resulting alliances provided the economic and military benefits of co-operation. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, European hunger for land had expanded dramatically, and the economic base of the colonies shifted from resource exports to domestic production, in particular agriculture. In the decades following the War of 1812, a period when the balance of military power shifted in favour of the colonists and the prospect of French-English (and British-American) war receded, the utility of strategic alliances was diminished. Co-operation with the Indian population gave way to the emerging business of nation-building and to direct competition for land and resources. Settlers began to view aboriginal people as a problem.

The Indian Problem was a direct outcome of the national project — the effort to forge a contiguous continental nation from sea to sea. Indians were seen as presenting an obstacle both to the physical and moral expansion of Christian civilization and industry. Although less of a mortal danger, the Indian population continued to be a threat to westward expansion, as the 1885 rebellion demonstrated. In the final quarter of the nineteenth century, Canada undertook a series of initiatives designed to pacify the Indian population, thereby to secure possession and control of the land and its resources. These initiatives included the drafting of legislation (foremost among which, in this context, are the 1876 Indian Act and the Dominion Lands Act of 1872), the building of a railroad, the establishment in 1873 of a security force — the Royal Canadian Mounted Police — and the negotiations of the numbered treaties*

Keenly aware of the changes underway, aboriginal people once again turned to the making of treaties as a tool to secure the means of their livelihood. While many settlers had come to regard Indians as an impediment to progress, aboriginal people continued to seek out the mutually beneficial alliances that had long served them in times of war and stress. To this end, the indigenous negotiators of the numbered treaties pressed their interlocutors for good faith commitments to provisioning Indians with the practical skills they would need in the years ahead. As the land base of aboriginal nations contracted and the means of subsistence receded, leaders turned to education as one of the more promising opportunities. [For a more detailed analysis, see J.R. Miller Shingwauk’s Vision, and “A Vision of Trust: The Legal, Moral and Spiritual Foundations of Shingwauk Hall” by Jean L. Manore in Native Studies Review 9, no. 2 (1993-1994) 1-21.]

The Government had little interest in long-term commitments and agreements. As soon as the treaties were concluded, federal officials turned their attention to absolving themselves of their pecuniary and administrative entanglements. Indians wanted education not to displace or overwhelm their own traditional knowledge, but rather to help them sustain their cultures and languages and ceremonies into the new order. The federal government however considered all things Indian to belong to the past and to have no place in the future. The official policy of Canada was to assimilate the Indian — to make him into a law-abiding, industrious subject of the Crown, no different from any other citizen. Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, summed up the Government’s position when he said, in 1920, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. […] Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian Question and no Indian Department.”

Education of the Indian as a means of assimilation had long been a subject of polemic throughout the Dominion. In 1842, the Bagot Commission produced one of the earliest official documents to recommend education as a means of solving the Indian Problem. In this instance, the proposal concerned farm-based boarding schools placed far from parental influence. The document was followed, in immediate successive decades, by others of similar substance: the Gradual Civilization Act (1857), an Act for the Gradual Enfranchisement of the Indian (1869), and the Nicholas Flood Davin Report of 1879, which noted that “the industrial school is the principal feature of the policy known as that of ‘aggressive civilization.’” This policy dictated that

the Indians should, as far as practicable, be consolidated on few reservations, and provided with “permanent individual homes” ; that the tribal relation should be abolished ; that lands should be allotted in severalty and not in common ; that the Indian should speedily become a citizen […] enjoy the protection of the law, and be made amenable thereto ; that, finally, it was the duty of the Government to afford the Indians all reasonable aid in their preparation for citizenship by educating them in the industry and in the arts of civilization.

A product of the times, Davin disclosed in this report the assumptions of his era – that “Indian culture” was a contradiction in terms, Indians were uncivilized, and the aim of education must be to destroy the Indian. In 1879 he returned from his study of the United States’ handling of the Indian Problem with a recommendation to Canada’s Minister of the Interior – John A. Macdonald – of industrial boarding schools.

The assumptions, and their complementary policies, were convenient. Policy writers such as Davin believed that the Indian must soon vanish, for the Government had Industrial Age plans they could not advantageously resolve with aboriginal cultures. The economic communism of Indians – that is to say, the Indians’ ignorance (from a European perspective) of individual property rights – was met with hostility by settlers eager for ownership of the land. Colonization required the conversion of Indians into individualistic economic agents who would submit themselves to British, and later, Canadian institutions and laws.

In the years leading up to the numbered treaties, the Government of Canada had little incentive to burden itself with the vast and potentially expensive task of educating the Indians scattered throughout its territories. Although in theory such an initiative may have been appealing, in practice it posed a series of administrative and logistic challenges. Nonetheless, and whether they welcomed this fact or did not, the treaties had drawn the officials of the bureaucracy into the business of education.

At the same time the federal government was contemplating its bureaucratic challenges, the denominations – Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist and Presbyterian – were eager to obtain a sufficient and predictable source of funding for their educational undertakings among the Indians. For decades, the various orders and sects and societies of the respective churches had been operating their orphanages, hostels, boarding, industrial and residential schools on the lean and precarious revenues of private subscriptions.

The work of fundraising was relentless and typically yielded insufficient resources. Petitions for subscription often involved the work of semi-formal grassroots organizations like the women’s auxiliaries, who sought financial support for missionary work by holding fund-raising meetings in the homes of well-off individuals. A presentation on the accomplishments and challenges of religious missions abroad would be followed by a call for donation. These activities continued into the twentieth century, and indeed to the present day, but by the nineteenth century religious groups became convinced of the necessity for a larger and more predictable funding base. To this end they became eager to draw the Government of Canada into a formal funding partnership.

The provisions of the numbered treaties presented the churches with their opportunity. The now-familiar, triangular relationship — between aboriginal peoples, religious entities, and the federal government — was forged. The churches secured a per-capita grant for the work they were already undertaking, and the government divested itself of the day-to-day burden of managing an Indian educational system. Under the terms of the partnership, Canada provided funding and set the standards and legislative framework of the Indian Residential School System, and the churches hired the staff and supervised school operations. The Government found a willing partner in the work of carrying out its assimilative agenda, and the churches received aid in its effort to Christianize the Indian. Both partners eagerly pursued a shared vision of a nation marching forward on the road of progress.

Lost in this Church-Government relationship were the spirit and intent of the treaties and the interests of aboriginal people. Instead of receiving the skill-oriented education they had negotiated, aboriginal people found themselves the objects of an aggressive Christian-based campaign of State-supported assimilation. The aspirations of government and churches were accommodated, but for indigenous peoples the Indian Residential School System represented a shocking, painful, and ultimately destructive violation of trust. The co-operative and mutually beneficial relationships with which we began this chapter had given way to exploitative relationships of opportunism and conquest. That, reduced to its core, is the story of Canada’s Indian Residential School System.

*

Over the decades, the Indian Residential School System comprised a diverse set of arrangements including industrial and boarding schools, Inuit tent camps, and hostels adjacent to school buildings. Today the Government of Canada officially recognizes 139 residential schools (located in all provinces and territories except Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick) as belonging to the system, over half of which were operated by one of the many Roman Catholic orders active in the country. (The Roman Catholic Church, which is to say the Vatican, is not subject to Canadian law — the legal representative of the Catholic Church within Canada is the Corporation of Catholic Entities.) The remaining schools were operated by the Church of England (later the Anglican Church of Canada), the United Church of Canada (formed by the United Church of Canada Act on June 10, 1925, by union of members of the Methodist Church of Canada, the Congregational Union of Canada, and 70 per cent of the Presbyterian Church), the Presbyterian Church of Canada, and the Baptists. In 1931, the number of concurrently operating Indian residential schools peaked at 80, with an enrollment of approximately 7,831.

[The number of schools operating declined from this point, while total enrolment rose. In 1931, 17, 163 Indian students were enrolled if one includes the day schools. See here for example.]

The Indian residential schools were distributed geographically as follows:

Alberta: 25

British Columbia: 18

Manitoba: 14

Northwest Territories: 14

Nova Scotia: 1

Nunavut: 13

Ontario: 18

Quebec: 12

Saskatchewan: 18

Yukon 6

[Source: the official Court website for the settlement of the In re Residential Schools Class Action Litigation retrieved on January 8, 2013.]

The following, from the 1931 Annual Report of Indian Affairs, provides a breakdown of the residential school system by denomination:

Generally speaking, residential schools enjoyed a particularly successful year. At these institutions, emphasis is placed on vocational training, religious instruction and the care of health. The various churches, as shown hereunder, co-operate with the department in the residential school activity, to the advantage of all concerned.

| Roman Catholic |

44 residential schools |

| Church of England |

21 residential schools |

| United Church |

13 residential schools |

| Presbyterian |

2 residential schools |

| Total |

80 residential schools |

Indian schools follow the provincial curricula, but special emphasis is placed on language, reading, domestic science, manual training and agriculture. Frequent inspections are made by officers of the department. In addition, public and separate school inspectors visit all classrooms, except in the provinces of New Brunswick and British Columbia, where there are special Indian school inspectors.

As early as the first Indian Act, in 1876, the government legislated provisions concerning the education of Indian children. However, not until the 1920 amendments to the Indian Act was attendance at a residential school made compulsory, with the government assuming the right to apprehend children:

The recent amendments give the department control and remove from the Indian parent the responsibility for the care and education of his child, and the best interests of the Indians are promoted and fully protected. The clauses apply to every Indian child over the age of seven and under the age of fifteen.

If a day school is in effective operation, as is the care on many of the reserves in the eastern provinces, there will be no interruption of such parental sway as exists. Where a day school cannot be properly operated, the child may be assigned to the nearest available industrial or boarding school. All such schools are open to inspection and must be conducted according to a standard already in existence. A regular summer vacation is provided for, and the transportation expenses of the children are paid by the department.

In 1930, the compulsory education clause of the Indian Act was again amended, making it possible “to compel the attendance of every physically fit Indian child between the full ages of 7 and 16 years.” Furthermore, according to the Department of Indian Affairs Annual Report, “in very special cases, the Superintendent General may direct that a pupil be kept in school until he has reached the full age of 18 years. The usual practice at Indian residential schools is to encourage pupils to remain until they are 17 or 18.”

More children were enrolled in a residential school than attended regularly, some children for instance accompanying their parents on seasonal hunts and trap lines. According to government records, average attendance in 1891 was 80.03%, rising to 88.33% in 1931. The principal interest of school administrators was in enrolment: the per capita formula meant that income from government would be based upon the number of registered students. As a result, administrative efforts tended to focus more upon the processing of children as against the pursuit of truants. With the federal legislation of compulsory attendance came resources to employ a more aggressive campaign of seizing, invigilating and retaining Indian children. Unco-operative parents were in many cases imprisoned, and run-away children — an ever-present reality leading to many deaths, particularly in Winter — were pursued by police and/or church employees. Compliance was enforced in other, more indirect ways. One example may be derived from the Indian Agent Hayter Reed, whose withholding of food rations from troublesome individuals earned him the nickname “Iron Heart.”

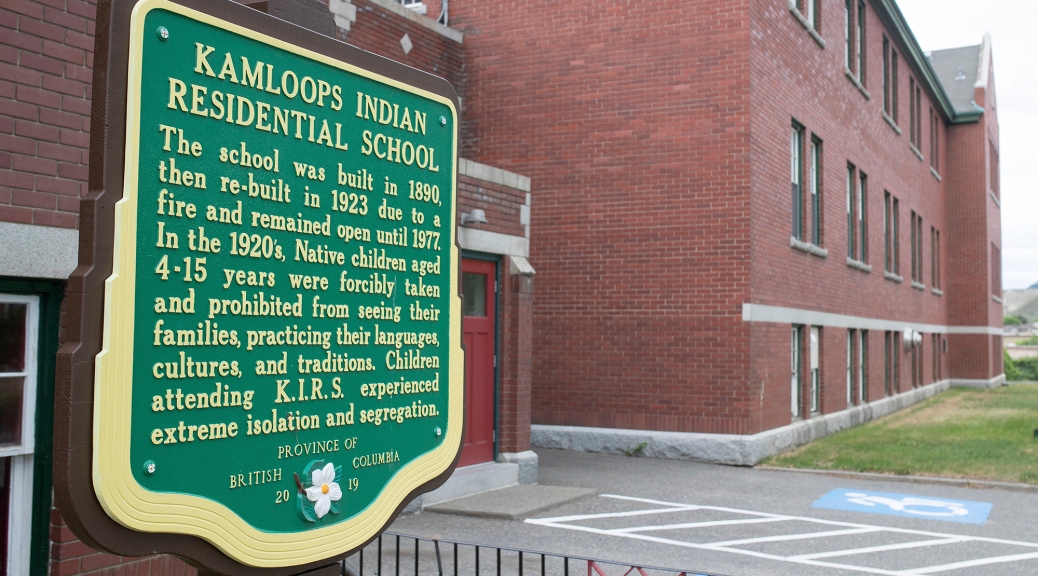

The Indian residential school was an institution enveloping every aspect of a child’s life. Having been taken from home and family and community to be placed on a boat or plane or train for a journey of hundreds and in some cases thousands of kilometres, and in many cases separated from siblings who were sent to other distant residential schools, these first waves of children arrived disoriented and confused to an alien landscape of concrete, nuns, priests, inscrutable words and strange religious iconography. Noticing a bleeding man nailed to a cross, children would infer for themselves a similar fate. [See for instance the interview with Ralph Johnson in Nadia McLaren’s 2008 documentary Muffins for Granny: “the first thing I saw was this huge, ah, sculpture or image of a man they had nailed to the cross. And, ah, I didn’t know what it was. I was thinking, you know, is this what they’re going to do to us?”] Stripped of their clothes, the children would then undergo a routine initiation — scrubbing, head shaving, and assignment of a uniform, bed, and number. It would be by this number that the children would henceforth be known. Alone and far from the comforts and familiarity of home, children would struggle with the fears, loneliness, and deprivations which attend incarceration within a state institution.

Every moment of every day in the Indian residential school was regimented. The routine was divided along gender, the typical day of a boy focusing on farming and stock raising, and the day of a girl on “domestic science.” Accordingly, the boys’ mornings began as early as 5:30 with the feeding of animals, milking of cows, and otherwise tending to the animals. The girls would rise at roughly the same time, or shortly thereafter, to conduct the morning’s household chores. Following this would be the long queues for washing and a breakfast of porridge and bread, after which came morning religious and academic studies. Then a lunch, typically soup, stew or sandwiches. The afternoons were dedicated to work — farming, house cleaning, sewing and general maintenance, again organized according to gender. The labour of children was critical to the economics of the residential school. The produce of the school (including staples such as milk and potatoes, as well as handicrafts) was sold, the profits applied to the costs of administration. The children themselves encountered hunger as a normal condition, so much so that it was common for them to sneak into the fields at night to dig up and eat whatever could be had from the ground. The afternoon’s labour concluded, children would have some time to themselves before a dinner of meat and root vegetables, and perhaps a snack of fruit when in season. The evening would include time for recreation followed by evening prayer and a bed time of 9.

As the years progressed, the schedule evolved to keep up with the broader changes in the culture. More time was accorded to recreation, and many schools added sports teams, brass bands, dances and movie nights to their regular activities. By mid-century a full day of study, focused on core subjects like math and science, was not uncommon.

From the beginning, the schools exhibited systemic problems. Per capita Government grants to Indian residential schools — an arrangement which prevailed from 1892 to 1957 and which represented only a fraction of the expenditures dedicated to non-Aboriginal education — were inadequate to the needs of the children. (As noted earlier, child labour supplemented the government’s contributions.) Broad occurrences of disease, hunger, and overcrowding were noted by Government officials as early as 1897. In 1907 Indian Affairs’ chief medical officer, P.H. Bryce, reported a death toll among the schools’ children ranging from 15-24% – and rising to 42% in Aboriginal homes, where sick children were sometimes sent to die. In some individual institutions, for example Old Sun’s school on the Blackfoot reserve, Bryce found death rates which were even higher.

F.H. Paget, an Indian Affairs accountant, reported that the school buildings themselves were often in disrepair, having been constructed and maintained (as Nicholas Flood Davin himself had recommended) in the cheapest fashion possible. Indian Affairs Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott told Arthur Meighen in 1918 that the buildings were “undoubtedly chargeable with a very high death rate among the pupils.” But nothing was done, for reasons Scott himself had made clear eight years earlier, in a letter to British Columbia Indian Agent General-Major D. MacKay:

“It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habituating so closely in the residential schools, and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is geared towards a final solution of our Indian Problem.”

As a consequence of under-funding, residential schools were typically places of physical, emotional and intellectual deprivation. The quality of education was quite low, when compared to non-Aboriginal schools. In 1930, for instance, only 3 of 100 Aboriginal students managed to advance past grade 6, and few found themselves prepared for life after school – either on the reserve or off. The effect of the schools for many students was to prevent the transmission of Aboriginal skills and cultures without putting in their place, as educators had proposed to do, a socially useful, Canadian alternative. This predicament is vividly described by John Tootoosis in a biography which recounts his days at Delmas (or Thunderchild) Residential School, in Delmas, Saskatchewan:

… when an Indian comes out of these places [i.e. Indian schools] it is like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle. On one side are all the things he learned from his people and their way of life that was being wiped out, and on the other side are the whiteman’s ways which he could never fully understand since he never had the right amount of education and could not be part of it. There he is, hanging in the middle of two cultures and he is not a whiteman and he is not an Indian. They washed away practically everything from our minds, all the things an Indian needed to help himself, to think the way a human person should in order to survive.

No matter how one regarded it – as a place for child-rearing or as an educational institution – the Indian Residential School system fell well short even of contemporary standards, a fact recorded by successive inspectors. A letter to the Medical Director of Indian Affairs noted in 1953 that “children … are not being fed properly to the extent that they are garbaging around in the barns for food that should only be fed to the Barn occupants.” S.H. Blake, Q.C., argued in 1907 that the Department’s neglect of the schools’ problems brought it “within unpleasant nearness to the charge of manslaughter.” P.H. Bryce, whose efforts earned him the enmity of the Department (and an eventual dismissal), was so appalled – not only by the abuses themselves but by subsequent Government indifference as well – that he published his 1907 findings in a 1922 pamphlet entitled “A National Crime.” In the pamphlet, Bryce noted that

Recommendations made in this report followed the examinations of hundreds of children; but owing to the active opposition of Mr. D.C. Scott, and his advice to the then Deputy Minister, no action was taken by the Department to give effect to the recommendations made.

Bryce’s 1907 report received the attention of The Montreal Star and Saturday Night Magazine, the latter of which characterized residential schools as “a situation disgraceful to the country.” These publications, and others like them, make it clear that the conditions of the schools were generally knowable and known, not only by officials of the church and government, but by members of the public-at-large.

Because low regard for aboriginal languages and cultures, and for the children themselves, shaped Canada’s policies toward Indians, matters continued as before despite internal reports and published accounts of abuse. In 1883, the Yakima Indian Agent and veteran of the Mexican and American Civil wars, General R. H. Milroy, was quoted in a British Columbia petition for industrial boarding schools as saying that “Indian children can learn and absorb nothing from their ignorant parents but barbarism.” The residential school system, designed to produce in the Aboriginal child “a horror of Savages and their filth” (in the words of Jesuit missionary Fr. Paul LeJeune), was rationalized by this contemptuous belief.

Individual beliefs about Indians, which in any case varied, did not determine the character of the individual schools. Nor were the conditions identical in each institution: students today recall diverse memories of both good and bad experiences, as well as good and bad teachers. Nonetheless, the widespread occurrence of certain residential school features suggests that structural elements were in effect. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) concluded in 1996 that the schools themselves were, for readily identifiable and known reasons, “opportunistic sites of abuse”:

Isolated in distant establishments, divorced from opportunities for social intercourse, and placed in closed communities of co-workers with the potential for strained interpersonal relations heightened by inadequate privacy, the staff not only taught but supervised the children’s work, play and personal care. Their hours were long, the remuneration below that of other educational institutions, and the working conditions irksome.

In short, the schools constituted a closed institutional culture that made scrutiny difficult, if not impossible. For staff the result was, in the words of RCAP, a “struggle against children and their culture […] conducted in an atmosphere of considerable stress, fatigue and anxiety.” In such conditions, abuses were not unlikely – a fact to which the experts of the day attested.

Then there are the testimonies of hundreds of former students, whose list of abuses suffered includes kidnapping, sexual abuse, beatings, needles pushed through tongues as punishment for speaking Aboriginal languages, forced wearing of soiled underwear on the head or wet bedsheets on the body, faces rubbed in human excrement, forced eating of rotten and/or maggot infested food, being stripped naked and ridiculed in front of other students, forced to stand upright for several hours – on two feet and sometimes one – until collapsing, immersion in ice water, hair ripped from heads, use of students in eugenics and medical experiments, bondage and confinement in closets without food or water, application of electric shocks, forced to sleep outside – or to walk barefoot – in winter, forced labour, and on and on. Former students concluded in a 1965 Government consultation that the experiences of the residential school were “really detrimental to the development of the human being.”

This system of forced assimilation has had consequences which are with Aboriginal people today. Many of those who went through the schools were denied an opportunity to develop parenting skills. They struggled with the destruction of their identities as Aboriginal people, and with the destruction of their cultures and languages. Generations of Aboriginal people today recall memories of trauma, neglect, shame, and poverty. Thousands of former students have come forward to reveal that physical, emotional and sexual abuse were rampant in the system and that little was done to stop it, to punish the abusers, or to improve conditions. The residential school system is not alone responsible for the current conditions of Aboriginal lives, but it did play a role. Following the demise of the Indian residential school, the systemic policy known as “aggressive civilization” has continued in other forms.

Many of the abuses of the residential school system were, we should keep in mind, exercised in deliberate promotion of a “final solution of the Indian Problem,” in the words of Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott. If development of the healthy Aboriginal human being meant respect of Aboriginal cultures, then indeed the regimented culture of the schools was designed precisely to be detrimental. As noted in the 1991 Manitoba Justice Inquiry, the residential school “is where the alienation began” – alienation of Aboriginal children from family, community, and from themselves. Or to put the matter another way, the purpose of the schools was, like all forced assimilationist schemes, to kill the Indian and save the man – an effort many survivors today describe as cultural genocide. [The phrase “Kill the Indian, and save the man” is often misattributed to officials within the Canadian government. Its source is Captain R.H. Pratt, an American soldier and founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In June 1892, Pratt delivered a speech entitled “The Advantages of Mingling Indians and Whites” to the National Conference of Charities and Correction in Denver, Colorado. In this speech, he said:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”]

*

By the 1940s, government officials were shifting their focus from the segregationist approach of the residential school to integrationist arrangements such as the placement of Indians within the public school system. In 1934, the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Harold W. McGill, noted that “there is no foundation for the common belief that the Indians of Canada are a vanishing race. The census which is taken at five-year intervals has shown a substantial increase in each of such periods during the past fifteen years at least, and the statistics may now be regarded as reliable. The birth rate continues to be high, and the death rate is definitely diminishing.”

Although on its surface this change of direction — from residential to public schooling — suggests a change of policy, assimilation remained the ultimate objective. Not only was the Indian Problem not being solved, with every passing year there were more Indians under the auspices of the Indian Act and the Indian Department. Assimilation, it appeared, would require another approach.

The Indian Residential School System would continue for three more decades. Although enrolment into this system would increase, after 1932 the total number of schools within it stopped growing. The Trudeau government’s 1969 “Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian policy” [the infamous “White Paper”] reiterated many of the points made in the October 1967 Hawthorn Report, which called for “complete school integration.” The White Paper outlined the way ahead as Canada envisioned it, again with a view to extinguishing the treaties and the relationship articulated therein:

The significance of the treaties in meeting the economic, educational, health and welfare needs of the Indian people has always been limited and will continue to decline. The services that have been provided go far beyond what could have been foreseen by those who signed the treaties.

As the earlier comments of Duncan Campbell Scott, and others, disclose, the Government of Canada assumed from the beginning the view that the treaties were a temporary expedience on the way to absorbing Indian peoples and assuming control of the land. On April 1, 1969 Trudeau terminated the formal church-government partnership, and the federal government assumed administrative control of the Indian residential schools. This marked the official end of the Indian Residential School System. Throughout the 1970s and beyond, the schools were closed and responsibility for on-reserve education was transferred to local Indian band councils while the provinces took over the work of the off-reserve education of Indians. Gordon’s Indian Residential School, in Saskatchewan, was the last federal-run Indian residential school. Managed by the federal government at the band’s request, it closed in 1996.

With few exceptions, the men and women who created and sustained Canada’s Indian Residential School System believed that the policy of “aggressive assimilation” (as Nicholas Flood Davin, following the example and policies of US President Ulysses S. Grant, termed it) was benevolent and forward-looking. The absorption of the Indian into Canadian society, a necessary part of the effort to possess the land and resources and to build a nation-state, was the desired outcome of policies and the final solution of the Indian Problem envisioned by, among others, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott. The policy of assimilation neither began nor ended with the Indian Residential School System. The program of assimilation continues to this day, as does the project of nation-building, from sea to shining sea.

***

Study of the Indian Residential School System poses special challenges to the student of history. Those who seek representations of “what really happened” should do so under advisement. For example, what do the archival photographs of residential schools and students capture? Often not the authentic experiences of the children, but rather the policy of assimilation in action. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the taking of one’s photograph was a rare and special occasion. The administrators of the schools put considerable effort into crafting the best possible image of their institutions on film. In many archival photographs, the students pose in laboured formations, well-manicured and dressed in formal clothing they would have worn only on such occasions. The photos were informed by multiple desires and purposes, chief among them the desire to impress the distant Ottawa bureaucrats and the missionary societies whose continued financial contributions the administrators greatly desired.

Another way of putting the matter is to observe that the historical record preserves the viewpoints often of the Government and the churches. We see reflected in the historical record the self-image of these institutions. Most of the individuals who worked in the hostels, schools, orphanges and boarding houses were kind and well-meaning. Many sacrificed to undertake this work. They were proud of their accomplishments, and it is the accomplishments which the archive captures.

The Indian Residential School System provokes the question, Is forcible assimilation a good policy? Was it morally right in the past, and is it morally right now? It is one thing for a member of a culture to choose assimilation into another culture. It is quite another matter when a dominant culture systematically forces assimilation upon another group. This process has endured under many names, for examples colonization, progress, advancement, imperialism, charity and cultural genocide. In Canada, residential schools were one instrument of advancing assimilation of indigenous peoples. Others have been the Pass and Permit System, the mass adoption of indigenous children into non-indigenous homes (a policy known today as the “Sixties Scoop”), and the displacement of traditional leaders in favour of a Chief and Council system of colonial governance. These and other policies have been features of the Indian Act, which remains to this day the legislative instrument governing the lives of Aboriginal people in Canada. The Indian Act not only determines the rights of Indians but defines who and who is not an Indian in Canada. In short, the very Act from which the Indian Residential School System derived its force and legitimacy remains in place. Specific policies have come and gone, but the underlying goal of assimilation, and the overriding Indian Act, continue.

*

The nature of the relationship between aboriginal peoples and the government of Canada may be characterized in many ways, but it was above all the desire for justice and reparation which fueled the healing movement in the decades following the demise of the Indian Residential School System. The trust of aboriginal people was violated throughout the roughly eighty years the residential school system endured, as generations of children were subjected to many forms of systemic institutional abuse, creating the historic trauma which remains with us today. Not only the children suffered. The parents and grandparents and communities left behind were also devastated.

It is important to realize that residential schools were only one symptom of the imbalanced relationship between aboriginal people and the Government of Canada. To address only residential schools, even in a comprehensive manner, is to treat a symptom. Land, languages, cultures, mental and physical health, have all suffered, and continue to suffer, as a result of this broken relationship.

Furthermore, considering Indian residential schools as an instance of failure to honour the spirit and intent of a negotiated relationship exposes the relevance of the issue to the contemporary individual. Policies come and go, but the historically-grounded relationship between aboriginal peoples and the crown remains. The policy of forced assimilation has not only devastated aboriginal people, it has violated trust. As a result, the residential school legacy of chronic addictions, community violence, suicide, mental illness, broken families, mistrust of leadership and authority, poverty, and shame persist, as does the political impasse.

The theme of relationship shows the way out of this legacy. It binds past, present, and future. It is the underlying reality. That is one reason why, for instance, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples chose as the title of the Final Report Summary, “People to People, Nation to Nation.”

In the introduction to that publication, the Commissioners wrote,

The story of Canada is the story of … peoples trying and failing and trying again to live together in peace and harmony. But there cannot be peace or harmony unless there is justice. It was to help restore justice to the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Canada, and to propose practical solutions to stubborn problems, that the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was established.

Ten years later, and more, this remains the case.

* “Numbered treaties” refers to 11 negotiated agreements signed between aboriginal people and the federal crown, between 1871 and 1921.

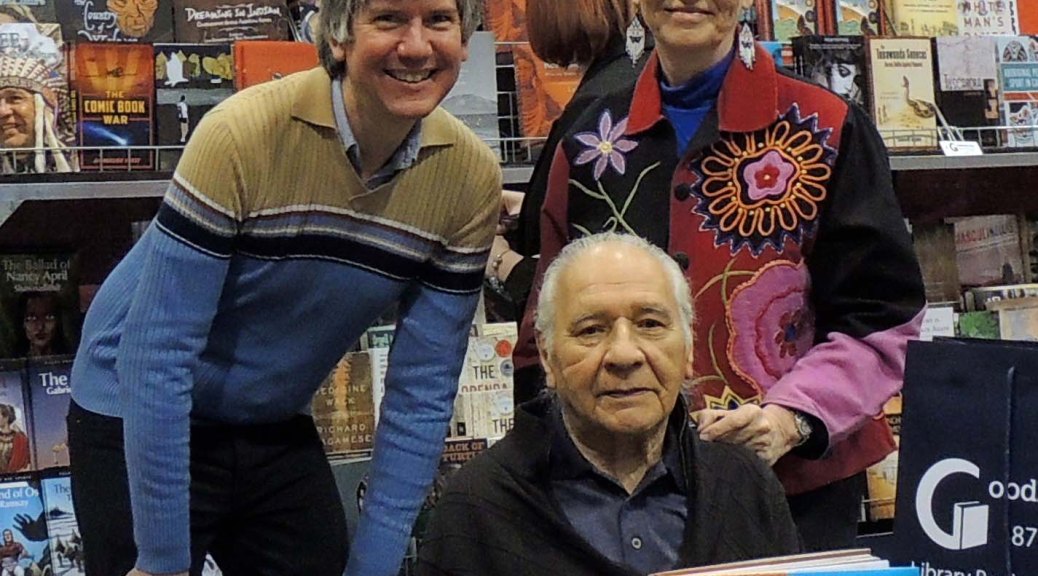

My Fall 2014 book “Residential Schools, With the Words and Images of Survivors, A National History,” is available from Goodminds. Order by phone, toll-free 1-877-862-8483.