The worst thing that could happen would be for the Canadian public to forget this painful history

The worst thing that could happen would be for the Canadian public to forget this painful history

WAYNE K. SPEAR | SEPTEMBER 30, 2021 • CURRENT EVENTS

In October 1990, Canadians were shaken — much as they were by the recent discovery of unmarked graves at former residential schools — when Phil Fontaine opened the nation’s eyes to the horrors that took place at those schools and the long-lasting trauma that resulted.

Yet Fontaine later told me that the events of that month happened by accident. He’d said during a meeting of the Assembly of First Nations that it was necessary for the organization “to deal with an issue that was like a plague in our communities … residential schools, and the abuse that went into those schools.”

On the way home, a Globe and Mail reporter who’d been at the meeting approached Fontaine at the airport. They had a brief conversation, and the next day Fontaine woke to discover his words were front-page news.

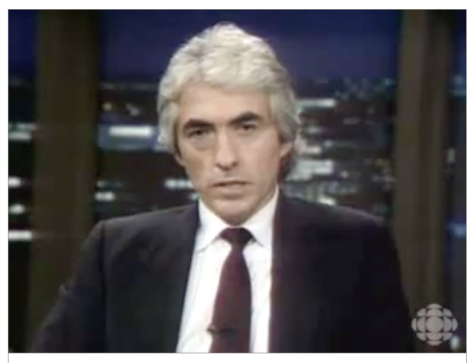

Fontaine would be interviewed about his experiences many more times. His interview with Barbara Frum, on Oct. 30, 1990, is perhaps the most notable. Many who were in an Indian residential school system have told me that Fontaine’s willingness to speak out on the issue gave them the courage to do the same.

No one was talking publicly about the Indian residential school system before then. Hardly anyone, beyond those who were there, knew anything about it. Between 1907 and 1940, there had been a handful of newspaper articles about the schools, with headlines like Canada Deserts Her Children and Schools Aid White Plague — Startling Death Rolls Revealed Among Indians — Absolute Inattention to the Bare Necessities of Health. Yet if Canadians were shocked at the time, they soon got over it, and quickly forgot.

In 1990, the stories returned, this time told by Indigenous people themselves. By the end of the decade, Canadians who wished to could find a good many books on the residential schools. In the early-to-mid 2000s, residential school lawsuits were commonplace news. Then came the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. And after this, the prime minister apologized and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was set up.

While the current federal government has squandered much of the goodwill it amassed early in its mandate, with promises of a new and sunny relationship with Canada’s First Nations, not everything is bad. Canada, for example, is unlikely to return to the era of universal ignorance about residential schools.

Anyone who dismisses the substantial achievement this represents disrespects the residential school survivors who for years dedicated themselves to a campaign of public education. As a result of their efforts, there is a consensus now that the experiences of those who attended residential schools ought to be heard and respected, and that those who did not survive the schools should somehow be recognized.

There is, of course, more work to be done. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) provided direction with its 94 calls to action. Among them is call to action number 80, which urged the government to designate a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The selection of Sept. 30 reflects the fact that this was the time of year when children were transported to the schools, in many instances hundreds and even thousands of kilometres from their homes.

The TRC envisioned the day as a statutory holiday and a time for reflection — and while this will not be the case for most Canadians (most provinces have not designated it as a stat holiday), the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation will evolve over time.

The worst thing that could happen would be for the Canadian public to forget this painful history. The formal designation of a day of observance and commemoration will serve the cause of remembrance, and that in itself is a good thing.