HUMAN REPRODUCTION is nothing if not a fertile topic, and our fecund media have underscored the point in the current case of US Senate hopeful, Todd Akin. At issue is his recent musing on the improbable concurrence of rape and conception, but there are other curious branches and sub-branches to the Akin story which are instructive. As the elections and leadership conventions approach, let’s peer down the avenues opened up by this case of unfortunate phrasing.

Category Archives: World

World politics and events.

Why the World Needs to Pay Attention to Pussy Riot

RICHARD BOUDREAUX’S euphemistic coverage yesterday, in the Wall Street Journal, of an “anti-Putin band” underscores the respective limits of polite discourse both here and in the former Soviet state. In Putin’s Russia, which is increasingly also the Mother Russia of the Orthodox Church, the cost of transgressing polite discourse’s state invigilated boundaries mounts.

The Arab Spring: in like a lion, out like a lamb to slaughter

ELECTORAL GAINS of the Muslim Brotherhood, most recently in Egypt and Libya, suggest that the Arab Spring came in like a lion and went out like a lamb to slaughter. Democracy, having conquered the Arab world, has yielded to Islamist autocrats its spoils.

Ratko Mladić: How Civilizations Tumble

ACROSS THE NEXT dozen or-so months, the Hague tribunal deliberating charges against former Bosnian Serb army commander Ratko Mladić will review a good amount of evidence, much of it rendered on videotape. The significance of this detail is easily missed if you are too young to have been an adult during the Bosnian War — but if you are of sufficient age, the richness of the record against Mladić constitutes a reminder not only of the crimes but of the character and indefensibility of the world’s slowness of response.

Belhassen Trabelsi — a criminal, not a refugee

THE RIVALRY BETWEEN Alberta’s Wildrose and Progressive Conservative parties at several points alluded to another contest, of Canada and Saudi Arabia in the designation of the world’s premier crude-yielding nation. There’s however another contest underway, crude in a differing sense, and concerning the harbouring of Tunisia’s former oppressors and exploiters.

Anders Breivik: not mad, but definitely a failure

It’s odd that a journalist writing of the Norway murders for the Christian Science Monitor would dwell upon Hindu nationalism while failing to consider the Knight’s Templar, but such was the case in the days following this depraved act of violence:

“Mr. Breivik’s primary goal is to remove Muslims from Europe. But his manifesto invites the possibility for cooperation with Jewish groups in Israel, Buddhists in China, and Hindu nationalist groups in India to contain Islam. … [His] manifesto says he is among 12 ‘knights’ fighting within a dozen regions in Europe and the US, but not India. It’s not known yet whether this group, which he calls the Knights Templar Europe, actually exists.”

Of course, a Knights Templar did exist in Europe — and while in business, they made a name for themselves throughout the Crusades of the Middle Ages. I mention this because Andrew Berwick (or as he is now known, Anders Behring Breivik) begins here also. His 1,500-page “manifesto” bears a Knight’s Templar motto on its frontispiece: “Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Solomonici,” or “The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon.” If you detect the aroma of the secret society in this, allow me to remind you that the Freemasons, historically hostile toward to Christianity, liberally appropriated the symbols of the Knights as well. It’s an old business, this cult stuff.

Having gone through his weird and self-absorbed work, I arrive at two observations. The first is that the man has long marinated in the fetish of fame, and the second is that he represents an extreme manifestation of views which are unfortunately not unfamiliar. The current trial of this paranoid also-known-as is in a sense giving him exactly what he wants — a global platform. This fame has been lamented by survivors such as Tore Sinding Bekkedal, but it should be kept in mind that the regrettable gift is extended under the principle that the other hand will simultaneously take. Here I refer to the fact that this lowlife thug employed murder as a cheap marketing trick, the object of which was to get you and me to pay attention to his message. Yes, he’s been given the audience, which is for him a victory of a sort. However, we were then expected under this arrangement to rally around his ugly cause, rather than denounce it. Today the fact that he is a chained man, rather than the hero he clearly wishes to be, is the only consolation in this depressing and disgusting matter. There was a time crusader and bigots of his stamp might actually lead, and how good for us the pseudo-politics of racial hatred and xenophobia are now so widely discredited.

There is some controversy whether or not Breivik is indeed of sound mind. His acts seem to some too mad to be the product of a rational intelligence. The remarkable thing about his writing however is how tediously ordinary it is in many respects. He includes for instance a Question and Answer section which divulges his sexual interests and (limited) experiences. The last eight pages are awkwardly postured photos. In each case Breivik strikes a note of pathos, apparently absorbed in the notion that everything he is and does is inherently interesting. The effort comes across less as madness than as self-importance further puffed up by his chauvinism.

There are further themes in the manifesto one cannot responsibly ignore. The man is a medieval Holy War nostalgist and a cultural Catholic extremist who admires the awful bigot Serge Trifkovic and who, if he could meet two famous persons, chooses the Pope and Vladimir Putin. (This too is covered in the Q & A.) The Pope is valued as a defender of Christian culture, seen by Breivik as under attack from bolshevism and radical Islam. The choice of Putin derives from similar logic, as well as from the recent Chechen Wars, and it is worth noting here the recent political and cultural resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Catholic Church, an institution deeply invested in the Russian dictator’s fortunes.

The last and certainly least of this trio, Serge Trifkovic, is a Serbian nationalist and a former Radovan Karadzic spokesman. A Republika Srpska hack, ethnic cleansing denier and Muslim hater, Trifkovic is most known (along with Walid Phares) for the development and dissemination of the “taqiyya thesis” — the idea that all Muslims are terrorists bent on world domination, required by their religion to lie about this essential fact. Today his tribal prejudices, which had ample indulgences during the Christian-fascist killings of Bosnian Muslims in former Yugoslavia, find a receptive audience among the far right all around the world. This is the sort of folk Breivik most admires.

So if he is mad — and I don’t for a minute think he is — he at least has the lucidity needed to expound at length his thesis. Putting it as plainly as I can, that thesis is as follows. The Christian world is under attack and may only be redeemed through a violent and atavistic effort to repel modernism, as manifested in the twin forces of Bolshevism/Marxism and liberalism. Note that this is the argument which gained an audience in the late Weimar Republic, excepting one important detail: anti-Semitism. Nowhere does Breivik stoop in this manner, and nor does he profess to admire Hitler or the Third Reich. (Mein Kampf comes up, but only to make the point that Goebbels’ propaganda techniques are today being employed by the multiculturalists.) Rather than the familiar scapegoating of the Jews we find instead the Islamic menace, which has the curious effect of aligning this proto-fascist with Israel. Do not be misled however by the character of the creed in this new political sleeping arrangement.

As a parting exercise, I invite you to submit to a thought experiment. Imagine if you will that Breivik’s war does arrive, and in the form for which he has committed mass murder. Whose side will you be on? I myself have no desire to be on either. Precisely the things I detest about jihadism I hate also about Breivik’s holy war and the thinly-veiled authoritarianism of those who have attempted to qualify or explain away his actions. By apologize I refer to those who have publicly denounced his methods only to then say “he has a point.” If you crawl even a bit into his head, you see that you can’t pick and choose so languidly: the disease of his worldview is down to the bone. Returning to the point at which I began, I observe with relief the failure of Berwick’s appeal to Hindutva chauvinism and every other kind of bigotry. His manifesto is a failure, and he is a failure also. Meanwhile the work of civilization — in whose service labour millions of Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, atheists, agnostics, and Hindus — marches forward. Amen.

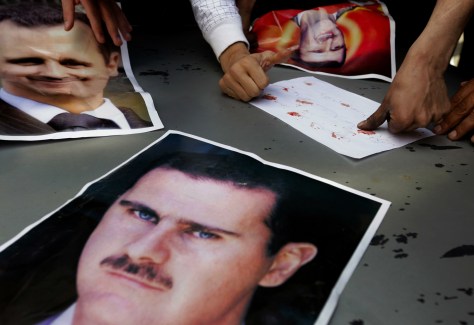

Where culture meets hypocrisy, you’ll find the Assads

As far back as Geoffrey Chaucer the English satirical tradition has made ample use of hypocrisy’s cousin, the euphemism. Human nature being what it is, the medieval Catholic Church settled upon niece and nephew as the most expedient designations of those otherwise inexplicable attachments to the celibate parish priest, bishop, and so on. Chaucer’s fourteenth century, as narrated in the brilliant Canterbury Tales, is arguably more worldly and cynical than the present. In any case, the non-alignment of pretense and reality is taken as granted.

The Guardian has now set to the wind a selection of emails between the Assads and their circle, access to which was made possible by a Syrian bureaucrat who presumably had had quite enough of the presiding hateful turd and his vain and pointlessly photogenic wife. In this email collection the theme of hypocrisy is amply represented, and who shall pretend surprise at that?

Look wherever you want: the blowhards exploiting in public the hot-button sentiments of anti-Western and anti-American righteousness, as well as their subgenres of sexual immorality and tribal supremacy, will as a rule be found in private to have inclinations of a contrary sort. This principle applies as far away as Abbottabad and as near as Washington D.C., comprising Osama bin Laden’s recently discovered suburban pornography collection as well as the cheap motel quickies of American family values congressmen.

Those who study the world’s geopolitical diversity soon acquire the critical habit of making analytical distinctions. “Muslim,” for instance, won’t do — and neither will Sunni and Shi’a. Even the subdivisions of Pashtun, Hazara, Ismaili, Ahmadi, Alawite, and so on, will sometimes not quite suffice. But, looking in another direction, you can aggregate quite a number of people under a common heading when the focus is the walk rather than the talk. That’s where most of us, in our shared humanity, appear a little less pure, less grand, less authentic.

In a malnourished country, Kim Jong-Il made himself conspicuously corpulent on a steady public diet of anti-Americanism paired with extravagant private consumption of Hollywood films and other imported delicacies. The Pyongyang dynasty’s under-acknowledged early patron, Mao Zedong, shared with the Kims this indulgence in private of things denigrated in public. The non-alignment of pretense and reality is not a universal principle, but it’s a common one.

The tools yielding glimpses into the Assad family’s private life (which would be none of our business, if their business wasn’t a matter of such willful and violent public imposition) also provide snapshots of the Internet activities of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and Iran and other epicentres of holiness. The little that we know suggests the broad appeal of decadent “Western” tastes. So it is across much of the culture war landscape. Who among us really doubts, to cite another timely example, that the American moral police and busy-bodies today agitating against access to contraception and abortion services will re-crunch the moral arithmetic when the calculations concern their own private rights and responsibilities?

The implicit point underscored by the Guardian is not that human beings are hypocritical (an ordinary, even tedious, observation), but that they have more in common than they have as differences. The differences are exaggerated and exploited by opportunistic bigots and chauvinists, like the governing Assad family of Syria. It may not encourage your inner humanist that Bashar al-Assad enjoys the same corporate pabulum which ten years ago you would have found on your teenager’s iPod. But at least you might draw some hope from the likelihood, made today more even more credible, that the culture war is a hollow confidence trick.

On the streets, people are fighting for the freedoms and dignities sometimes taken for granted in Western democracies. Meanwhile, in the palaces, the shortsighted overlords appeal to and indulge the most base of human impulses, denouncing “the West” in public as in private they shop and eat and otherwise enjoy the fruits of their enemies of convenience.

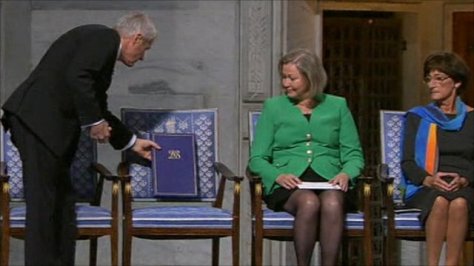

The ICC Works, But Only For Some

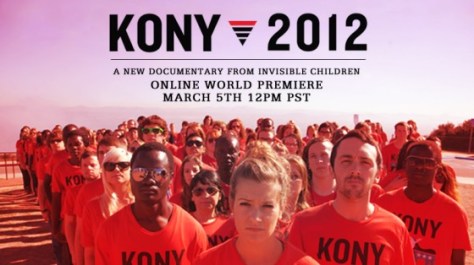

As if on cue, the International Criminal Court has delivered its first war crimes verdict before the #Kony2012 Twitter ink is dried and the template barbarism of a Ugandan fanatic has yielded its home above-the-fold.

I deploy the phrase ‘template barbarisms’ because the third-tier Congolese thug Thomas Lubanga, of whom I confidently assume you’ve heard little before today, resembles the now famous Joseph Kony, of which I’m equally confident you’ve heard a good deal. The tribal warlord trope is depressingly unoriginal, as are its signature crimes of rape, murder, and child abduction for the purpose of enforced military service. As the world considers this inaugural verdict of the International Criminal Court, some necessary criticisms will float to the surface. No one however can say that the ICC has no use: barbarism and fanaticism, like crime as a whole, never sleep.

The criticisms ought to get a good airing. In the late nineteenth century, the official and ancient boundary between civilian and soldier was erased. The parallel introduction of citizen-centered industrialized murder awoke the world to crimes so horrendous they could only be described as being “against humanity.” In both the first and second world wars, there were state organized campaigns of genocide. The Nuremberg trials established the principle of supranational — and even universal — justice, entrenching the ideas that there existed a civilized human community and that this community must stand vigilant against the work of racial cleansing and mass slaughter. But the world as a whole has not endorsed the practical measures which issue from these high-minded principles. And since the genocidaires tend to be the victors, they not only write the history, but they also have a role in determining the course of justice.

This deference to the good graces of sovereign nations is built into the Rome statute which established the ICC. Prior to the creation of this permanent international court, the tedious and drawn-out work of pursuing criminals and crimes against humanity had to be renewed with each fresh violation. Imagine beginning from scratch, with each outbreak of fanatical nationalism and tribal bloodlust from Yugoslavia to Rwanda to Iraq. Proceeding in this fashion, the pursuit of war criminals had become an inefficient and laborious exercise of reinventing the wheel. It’s therefore at least a matter of probable advantage that a standing court is ready for the inevitable business of entrepreneurial depravity.

It’s also encouraging, a decade into the ICC mandate, to see a known child predator brought to the courtroom. But that encouragement is watered down, for me at least, by the knowledge that other known abusers and exploiters of children continue to get a pass, for reasons which suggest a much deeper and cynical corruption. Rogue elements are brought to justice while certain respectable officials (see my comment above on the victorious genocidaires) evade their day in court. Who decides who is ripe for delivery to the Hague, and when? The answer is political leaders, who in some cases have their own ugly past, political agenda, and revisionist impulses.

This deference to national sovereignty was heavily lobbied by the permanent Security Council member of the United Nations, the United States of America. A non-signatory nation, the U.S. would only deliver its citizens voluntarily on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity. Non-signatory states may be pressured to oblige the court, but only by a directive of the Security Council members — who constitute the bulk of the non-signers. As a result, the court’s business is largely an inevitable matter of power politics, the list of those having a good and hard time of it having been drawn up by those self-guaranteed to go gently into the good night.

If you think this overly cynical, consider that the ICC’s investigations are currently limited to the world’s least politically-connected continent: Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir, former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Jean-Pierre Bemba, Liberia’s Charles Taylor, Uganda’s Joseph Kony, and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. There’s no shortage of crime in Africa, but there’s no monopoly either. The Kony 2012 video was at least correct in one of its assumptions. The politics of public opinion matter, even in the presumably impartial business of justice. It’s too bad that as the world is so suddenly engrossed in a viral video, there’s so much less attention to, and awareness of, an imperfect but fledgling effort to take the civilized world’s fight against crime to the next logical, and necessary, level.

Lessons of the ‘Stop Kony’ video — let the giver beware

A commonplace of our time is that social media, Facebook and Twitter and so on, connect and humanize us. Technology has put powerful tools into the hands of the humble, and the mighty are trembling: so goes the argument. Each time I hear this encouraging notion, into my thoughts comes a passage from the 1930 treatise, Civilization and Its Discontents. Surveying the early-twentieth century’s technological advances, the author — most known as the pioneer of psycho-analysis — interjects a “critical, pessimistic voice,” which notes that:

“If there were no railway to make light of distances, my child would never have left home, and I should not need the telephone to hear his voice. If there were no vessels crossing the ocean, my friend would never have embarked on his voyage, and I should not need the telegraph to relieve my anxiety about him. What is the use of reducing the mortality of children, when it is precisely this reduction which imposes the greatest moderation on us in begetting them, so that taken all round we do not rear more children than in the days before the reign of hygiene, while at the same time we have created difficult conditions for sexual life in marriage and probably counteracted the beneficial effects of natural selection? And what do we gain by a long life when it is full of hardship and starved of joys and so wretched that we can only welcome death as our deliverer?”

When Sigmund Freud wrote of “difficult conditions for sexual life in marriage,” he drew from personal experience. Indeed, he had near-to-hand many of the woes he describes. Yet I suspect most readers would think him unduly pessimistic about the potential of technology to make human lives better. What then would people say about the sparkly attitudes, and platitudes, of Jason Russell’s viral video “Kony 2012”, which constitutes an upbeat experiment in “changing the world”?

One advantage of the Internet is that questions of this sort have been rendered easily answerable. A quick Google search, and you know for instance that skeptics have already begun the work of evaluating the finances of the not-for-profit group Invisible Children, producers of the Kony video, yielding some questions in need of answers. The writer Musa Okwonga touches upon the major points in a Telegraph article — for example, Kony 2012’s gross oversimplification of Ugandan politics and the paternalism of Western celebrity do-gooderism. “On the other hand,” he notes, “I am very happy — relieved, more than anything – that Invisible Children have raised worldwide awareness of this issue.”

So am I, with my own reservations. I began this piece citing Freud because he establishes the tone of skepticism and the balancing of opposites necessary to the study of complex human issues. Of course I would prefer that peace in Uganda were achievable by means of a publicity campaign focusing on the “bad guy” Joseph Kony. But the central paradox of technological gain alluded to by Freud — the giving with one hand and taking with another — applies also to social media. I’ll phrase it as follows: There’s more information out there than ever before, only most of it is of doubtful use and value. Some may even be harmful. Here are things to consider if you plan on supporting the Kony campaign. These are not criticisms of Invisible Children or of the Kony 2012 video; they are practical observations. May they add some ounces of value to the global conversation.

Earlier I used the phrase “Ugandan politics.” This is itself a simplification and a not-very-helpful way of approaching Uganda. African politics, from the Maghreb to the Horn, are shaped by historical tribal systems of social organization. As we see in Afghanistan, another society built upon tribal systems, conflicts pay no heed to come-lately national borders. The internal affairs of Uganda are incomprehensible if you leave out, for example, Sudan. Kony, like any military chief, has a tribe-based network of support as well as of competition. If you are a Westerner this means you may have to dismiss the nation-state and nationalism as the chief units of political currency.

Another thing of which to be mindful is that aid is often exploited by dictators. Uganda has a large army, many times larger than the several hundreds thought allied to Kony. One has to ask (along with Okwonga) “Why hasn’t the much more powerful Ugandan army put an end to Kony’s atrocities?” A couple years ago, Jane Bussmann offered some insight to this and related questions in a piece published by the Telegraph. In her assessment, “Kony has been a smokescreen for profit. While the crackpot’s kidnapping was at its peak, thousands of children snatched, tortured and raped each year, the Ugandan army was using equipment bought with aid money to run illegal mines in Congo – duty free shopping.” Skeptics have long known that African misery is banked upon by corrupt leaders. They know that so long as things are bad for their people, aid money will flow into their hands. This is not an argument against aid — only against aid given uncritically, to the first person with a viral video or a catchy song or a celebrity sponsor. Let the giver beware.

My final point is that anywhere you look — Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Uganda — there will be longstanding and local groups of citizens resisting and fighting against powerful thugs and murderers. On this International Women’s Day, I note that women are commonly on the world’s democratic and anti-corruption fronts. This is because women and their children always suffer the most under oppressive arrangements. Any campaign anywhere that does not put the great bulk of your money — and whatever else it may muster — into the advancement of women’s health and education and political emancipation is not worth your patronage. One inevitable day the cameras and the Western troops and the cash dry up, and the local people are left to their own resources. This is when we find just how well- or ill-conceived our charity was. Better to get it right from the beginning.

The Triumph of America’s Booboisie

WELL BEFORE THE lapsed acronym RINO (Republican In Name Only) was re-popularized by California Reaganite Celeste Greig, Barry Goldwater had taken on the Rockefeller Republican, energizing a contemporary political trajectory whose crowning achievement was announced on July 27, 1980, by journalist Henry Fairlie:

The flame of intolerance rises from Koran burnings

NEWS OF THE Bagram Air Base Quran burnings, and the riots which have followed, reproduced the usual concern that perhaps no amount of evident contrition would prevent a violent response. Here is an illustration of the root of this anxiety, from a Reuters article of February 22: “Critics say Western troops often fail to grasp the country’s religious and cultural sensitivities. Muslims consider the Koran the literal word of God and treat each book with deep reverence.”

One Empty Chair and Many Empty Words

THERE ARE A few rules to which I’ve held myself as a professional speech writer. Do your homework, know and respect your audience and the protocols governing the occasion, and always prefer the plain truth that will not please your audience over nice-sounding and gratifying words that aren’t so. Or, as I’ve had occasion to summarize: it’s better to deliver bad news that you can guarantee than it is good news that you are confident you can’t.

The Conservative Party’s courting of China is shameful

I KNOW FROM experience the most efficient way to start a fist-fight in some circles is to use, without irony, the word evil. As in the phrase Axis of Evil. On this principle, George W. Bush was mocked for years by lefties who noted condescendingly (though correctly) that the President’s eyes were just a bit too close together for the nation’s good. One afternoon in the mid 90s, the man who would memorably link Iran, Iraq and North Korea — Bush Jr’s speechwriter, David Frum — passed in front of my car while I was at a red light. I confess repressing an urge to step on the gas. Some years on, however, I’ve a greater respect for Mr. Frum, and in part it’s due to the fact that I think there really is such a thing as evil, perhaps even in axis form.

What Mitt Romney’s returns tell us about the tax system

SOME WEEKS ago, having already absorbed a good many of Mitt Romney’s debate performances, New York Times columnist David Brooks noted the tinniness of the former Massachusetts governor every time the subject of money arose. Why can’t politicians talk plainly about money, and why does the subject of income tax yield so much verbal gymnastic?

Holding Out for the Bloodless Revolution

WITHIN THE space of days a bottomless media appetite will undertake the task of digesting 2011. A year of surprises, rebellion, and upheaval, its closing weeks now deliver the news that Václac Havel and Kim Jong Il have died. It is an offense against taste to fadge these two men in a final recollection, but it happens that mere chance has given us an occasion to ruminate on the just-maybes of 2012.