He was known and loved for his wit and warmth

✎ WAYNE K. SPEAR | JANUARY 22, 2020 • Obituaries

FOR YEARS from the late 70s on Monty Python’s Flying Circus greased the PBS pledge drive engine. That’s how I discovered the eccentric British comedy troupe featuring Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Terry Gilliam, and Terry Jones. The show opened a portal to a genre of distinct, English comedy, and working my way back from Python I discovered The Goon Show, Beyond the Fringe, The Frost Report and more.

The habit of working one’s way back is something I shared with Terry Jones. He was an Oxford English major whose love of Chaucer seduced him into Medievalism. This interest would yield numerous television skits as well as films like Monty Python and the Holy Grail. An accomplished historian, his work — whether as director, writer, or comedian — derived from a fascination and familiarity with the past. Combine this with a subversive sense of humour and the results are signature Jones sketches like “Elizabethan Pornography Smugglers” and a satire of the Aristotelian syllogism, from Holy Grail:

Sir Vladimir: So, logically …

Villager: (very slowly, with pauses between each word) If … she … weighs the same as a duck … she’s made of wood.

Sir Vladimir: And therefore …

Villager: A witch!

At the end of the 1960s Terry Jones was scripting similar absurdities for The Complete and Utter History of Britain and Twice a Fortnight. His collaborations with Michael Palin brought him into the orbit of John Cleese. Not that Cleese wasn’t already familiar with Jones’ work: both had been involved in The Frost Report months earlier, and the program Do Not Adjust Your Set had given Jones a good deal of exposure. All that aside, it was Palin who was top of Cleese’s list for a new program whose ideas for a name would include Toad Elevating Moment, Ow! — It’s Colin Plint, Owl-Stretching Time, A Horse, a Spoon and a Basin, and Gwen Dibley’s Flying Circus.

The Norman Invasion, according to Jones, from Twice a Fortnight

In 1969 the Chapman-Cleese partnership already went back some years, to Cambridge (where Eric Idle had also been a student), but so too the Oxford based partnership of Palin and Jones. The formation of Monty Python’s Flying Circus was a merger of almae matres, by means of which the American Terry Gilliam became an honorary Oxonian. Still without a name for their project, Cleese and the others set up a meeting with Michael Mills, head of comedy at BBC. Mills asked them: What sort of program do you have in mind? No one was quite able to say. Okay, said Mills, but I’m only giving you thirty episodes.

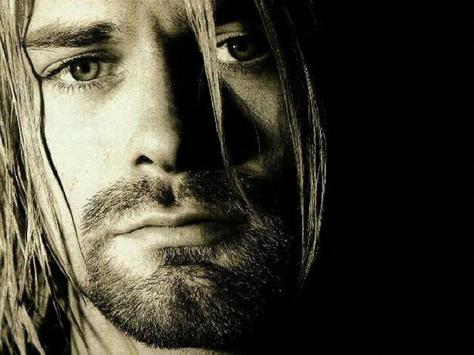

Those of us who delighted in the intelligent absurdity of Python will remember Terry Jones foremost as a Pepperpot; Mandy Cohen, the mother of Brian in the Jones-directed Life of Brian, was a variant of this recurring figure. Or perhaps he will be remembered most as the bowler-topped City Gent, a stereotype of the dull but respectable British businessman that was in decline even as the Pythons were satirizing it. Other honourable mentions include Mr Creosote (“it’s wafer thin”), Ron Obvious, and the Nude Organist. Like his colleagues, Jones played types rather than roles, and his was often the stuffy, repressed, and scandalized upper-class Englishman, bewildered and befuddled.

After Python, Terry Jones applied his talents to television and books, producing Terry Jones’ Medieval Lives and Who Murdered Chaucer?: A Medieval Mystery. When Monty Python reunited in 2014 for a live performance, Jones struggled to memorize his lines and read from a teleprompter. This was the first indication of his illness, later diagnosed as frontotemporal dementia. Of course no one failed to see the cruel irony of this disease, whose effects include loss of empathy and of the ability to speak and write, striking a man known and loved for his wit and warmth. ⌾

Gord Downie established himself as a symbol of Canada

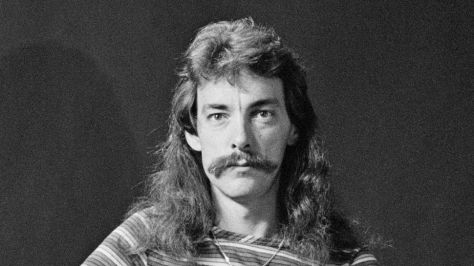

Gord Downie established himself as a symbol of Canada Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 1977. His “Flying V” guitar is featured in the band’s logo.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 1977. His “Flying V” guitar is featured in the band’s logo.