The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is an occasion for remembrance and also for understanding

✎ WAYNE K. SPEAR | SEPTEMBER 30, 2022 • Current Events

FATHER HUBERT O’CONNOR was principal of the St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School the year Phyllis Webstad was born. Six years later, in 1973, Phyllis arrived at the school wearing the new orange shirt she’d been given by her grandmother.

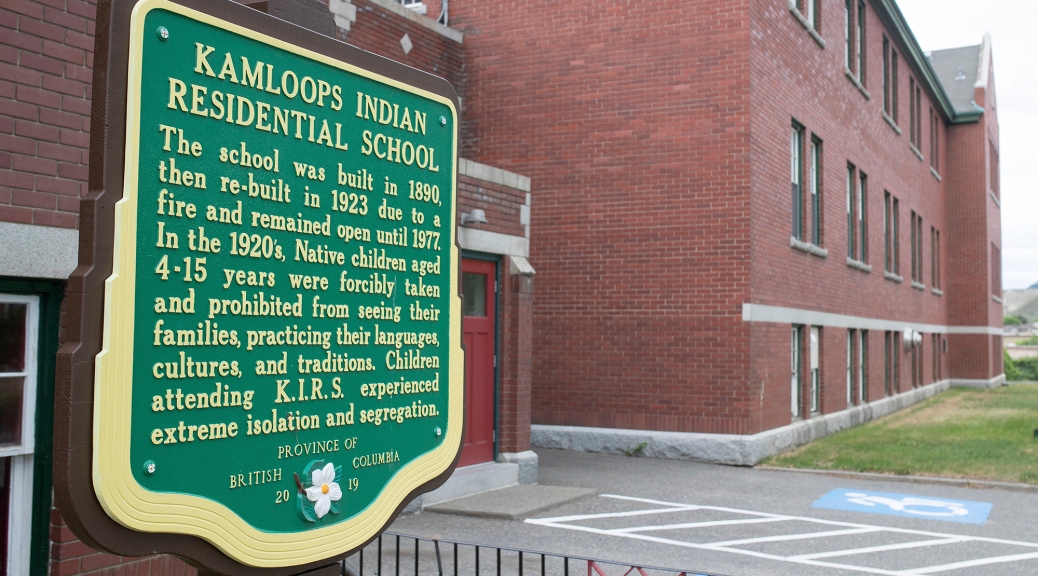

For decades Indian residential schools greeted their wards with a stock list of indignities: the children’s hair was cut, their clothing stripped away and replaced by a drab uniform, and numbers were assigned to serve henceforth in place of their names.

Phyllis’ new orange shirt was taken, and she never saw it again. At a May 2013 gathering of former St. Joseph’s students, her story became the inspiration for Orange Shirt Day. On May 28, 2021 a bill passed unanimously in the House of Commons, and shortly thereafter in the Senate, designating September 30 the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

September, the month of this national day of remembrance, is remembered by many Indigenous people as the time of year when those who got to spend summer at home returned to the institution. September is also remembered, with a degree of loathing, as the time when male children were sent into the schools’ fields to pick carrots and potatoes and to perform the many chores of harvest time.

But back to the future Bishop O’Connor. I began with him to underscore the fact that not so long ago predators abounded in the residential schools. At St. Joseph’s alone, dorm supervisor Edward Gerald Fitzgerald and Oblate priests Glenn Doughty and Harold McIntee were serial offenders.

In 1996 O’Connor was convicted of rape indecent assault. Doughty and McIntee served brief prison sentences for indecent assault, gross indecency, and buggery. An RCMP visit inspired Edward Gerald Fitzgerald to flee to Ireland in 2002, where local media reported him living in a “plush” Dublin suburb beyond the reach of Canadian authorities.

A good deal more of the St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School can be had from first-hand accounts — for example Bev Sellars’s memoir They Called Me Number One — as well as from research such as Elizabeth Furniss’s Victims of Benevolence: The Dark Legacy of the Williams Lake Indian Residential School and Margaret Whitehead’s 1981 study The Cariboo Mission: a history of the Oblates.

History, as the Final Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples says, “is not an attractive picture, and we do not wish to dwell on it.” But, as RCAP also acknowledges:

it is sometimes necessary to look back in order to move forward. The co-operative relationships that generally characterized the first contact between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people must be restored, and we believe that understanding just how, when and why things started to go wrong will help achieve this goal.

In other words, truth before reconciliation. We look back for one and forward to the other. The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is an occasion for remembrance and also for understanding.

On this year’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, many Indigenous people will be thinking of the children who suffered loneliness and deprivation, and who in some cases never got to return home. It is a sombre day of reflection but also a day to acknowledge that Indigenous people survived a system designed to erase their languages and cultures.

Today there’s an abundance of articles, books and video concerning every facet of the Indian residential schools, much of it in the voices of those who were there. In my experience they are more than willing to tell their stories. The simple act of listening is where both truth and reconciliation begin.⌾