I told the chiefs, “We’re not Indian Affairs. We’re not here to do things for you. We’ll help you do the things you want to do, and we’ll work hard.”

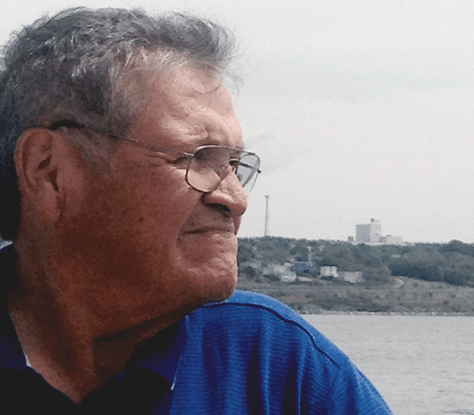

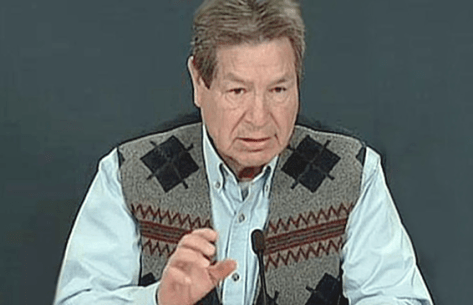

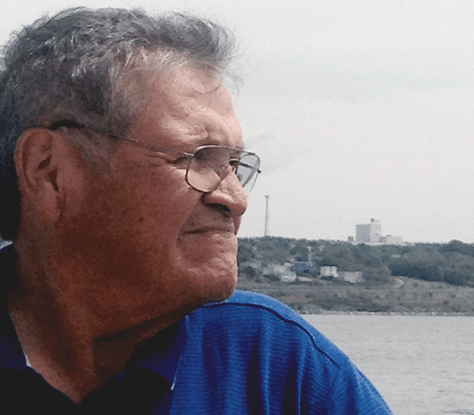

DELBERT RILEY is a First Nations leader from the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, west of St. Thomas, in southwestern Ontario. He was the leader of the Union of Ontario Indians and, from 1980–1982, National Chief of the National Indian Brotherhood (later known as the Assembly of First Nations). Now, at age 70, he is launching a London court case against the government and the church for the range of abuses and injuries he suffered in an Indian residential school. This interview was published in the Journal of Aboriginal Management.

Let’s begin with how you came to be a political leader.

What got me into it was that I lived in the States for ten years. I was very impressed with Macolm X and Stokely Carmichael. I read their stuff, and I thought, “Holy shit, these guys are trying to get something going on about racism in the United States.” I was very impressed, so I thought, “I have to go back to Canada. Maybe there’s something I can do to help my people.”

So I did. I had been a machinist. I enrolled in university and I got a job while I was there, doing land claims research. When I heard about the job, I thought, “I gotta grab that.” I was very aggressive. I spent months and months in the national archives, reading from when it opened to when it closed. It was just so interesting. I also learned how they thought. So my mind could go back in history. I could get in touch with the thinking. It also gave me one heck of a background and understanding of Aboriginal and treaty rights.

You learned a lot about history.

I’m a historian. My First Nation sent 124 warriors to fight with Chief Pontiac. He captured eight or nine of eleven forts. He killed everybody—men, women, children. This is part of history they won’t tell you. Britain issued the Royal Proclamation, I think, because of that. It doesn’t say that in any particular place, but that’s what happened.

In 1764 the Treaty of Niagara came out. This is probably the only time our people sat down and said, “Okay, we agree with you on this. We will come and fight with you if you respect our sovereignty.” This is always on my mind. The British wanted us as their allies, to fight against the Americans. Before that we fought off the white man for at least 300 years. We were always fighting for one major thing: our sovereignty—our independence, our ability to control our lands.

The Iroquois ran off the Americans at Niagara, not the British. The British sent 1000 troops to fight with us against the Americans on the Thames. But 600 gave themselves up to their cousins, the Americans, and the other 400 ran off to Toronto. The only ones fighting were Indians. At the Thames and Niagara we drove the Americans back. They hated fighting Indians.

After the War of 1812, they concentrated on taking our lands using every device they could, including racism. The Indian Act was developed from a multitude of laws they were already using in other countries at the time, especially Northern Ireland. So this is how the Indian Act was born. They sent over [Sir John A.] Macdonald to draw it up. He didn’t create it, but he took bits and pieces from all over.

Because our numbers were decimated by disease, we weren’t able to fight back, although we protested as much as we could against this Indian Act. It is the most devastating piece of legislation in the world. I tell people today that it was a model for South African Apartheid and for Nazi Germany.

Let’s talk about the background to Section 35 of the Constitution Act.

I was an activist. Because I was doing so many things for the Union of Ontario Indians, they said, “We want you to run as our leader.” I’d never been in politics. They put me in, and I changed the organization around. Well, anyway, I served a couple terms and I brought the organization from the red into the black. I started out with about eight staff who were ashamed to work there, and when I left they were all proud to be a part of that organization.

I told the chiefs, “We’re not Indian Affairs. We’re not here to do things for you. We’ll help you do the things you want to do, and we’ll work hard.” That’s the approach we took.

So all the constitutional talks were coming up. Trudeau wanted an amending formula, because for him it was embarrassing to have the constitution in England—the BNA Act. The only way to amend it was back in England. So he wanted changes. He was fighting the provinces, trying to get them to agree on what was the best formula. Fifty percent of the people? So many provinces? So much of the population? That kind of thing.

They finally did work out a formula that all reluctantly agreed to. In the meantime, things were happening. The Calder case, land claims, whatnot. I had this background in Indian rights. The national chief job was coming up—of what was at the time the National Indian Brotherhood. I was trying to pull all the leaders across the country together. I was telling them, “Look, we’ve got to get moving on this stuff.”

I had it in my mind from the early ‘70s that our best choice was to get entrenched in the constitution and have them recognize our rights in the highest law of the land. Then they couldn’t take it out. So I said I would support anyone who ran for the leadership to do this. None of them had the background I had, and none of them would run. I said, “If you’re not going to run, then I will. At least support me. I’ll put us in the constitution.” That was my platform when I ran for national leader.

It took me a year before we made the decision on the wording of the draft constitution sections. It was about nine pages. The Métis supported us, and I promised them that they would be in there, as well as the Inuit. But they didn’t do anything to support the kind of effort we did. We did one massive lobbying effort in Ottawa. I probably met every cabinet minister and the Prime Minister multiple times. I ate in all three houses of Parliament. I was a hard worker, and it took a long time and a lot of work.

How were the negotiations?

They wouldn’t go along with all of our draft, which if accepted would have set out a totally different system from what we have here. It would have been the kind of system we want, because everyone had contributed to that draft. All they would do in the government was put in four sections. The most important was section 35, the recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal treaty rights. I had a heck of a time. I had to appear before the committee, because there was no definition of Aboriginal people. But there was a precedent for this—they’d put words in the BNA that didn’t have a definition. So I was able to use that, and they finally accepted it.

In fact, they liked that it didn’t have a definition. They figured that Indian rights were what the St. Catherines Milling and Lumber Company v The Queen case had said in 1888, which was that we had usufructuary rights [rights of land usage, but not title]. This was their thinking. My thinking was, no, it’s more than that. John Munro, the Minister of Indian Affairs, called me over one day. I went to one of the restaurants. He said, “We’re getting so much flak from Alberta that we have to take your Aboriginal treaty rights protection out.” He said, “Here’s how we’re going to write it.” I took the paper and rolled it up in a ball, and I threw it at him and walked out.

What eventually brought about the acknowledgement of Aboriginal rights in section 35?

We had a big protest. But Alberta insisted that the word “existing” would go in. So it became existing rights. You see, the fight was all about resources. Alberta did this because of a case with the Maori in New Zealand in which the court determined that “existing” meant only from the time it went into the constitution. But when it got to the court here in Canada, existing included everything. So it was even better. [Laughs]

They called me into an all-party meeting at the eleventh hour. I think it was 11 pm. [Jean] Chrétien and I were screaming at one another. I said, “Goddamn it, we’ve got to have the wording in there.” “Okay,” Chrétien says. “But I want to take out the word Métis. Will you agree?” I thought, you cagey old bugger, you’re going to take it out and blame me. But I had a promise to the Métis that they would stay in there, and I’m a man of my word. So I said No: they stay in. I’m probably the father of Métis rights! [Laughs]

What was Jean Chrétien like?

He was tough. They were trying to figure out how to get rid of Indians and Indian rights. Trudeau was the same. We were working in the other direction. It was tough, but their racist attitudes were more out in the open. They downplayed us as inferior beings.

So, they put our rights in, but of course they didn’t plan on observing them. A lot of court cases came, something like 180 as of today we’ve won on section 35. I was in tremendous emotional pain at the 11th hour to go with only those four sections, and not everything we wanted. But I had to make that decision. It was my decision alone. I couldn’t even call anybody. There was no time, so I made the decision.

How was this received?

Of course I suffered the negative comments for years, people saying it’s not enough or it’s empty. There was so much controversy about section 35 I sort of got ostracized for years. They just kept me out of things. [Laughs] The jury was out, but as of the Tsilhqot’in [Aboriginal title] case this summer, the jury came in and exonerated me fully.

You must have known that this would happen all these years later—that you were laying the groundwork for the future.

Oh yes, I knew it. For sure. This is the basis for our Indian governance. This is going to be the basis for everything. The legal power is unlimited in my mind, even right now.

So in many respects this was a thankless task.

Oh, it is. But it had to be done. I did it. I have absolutely no regrets. If I had to do it again, I would. I’d do the same damn thing.