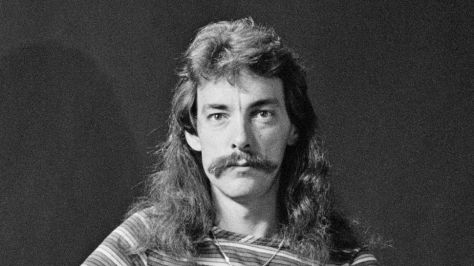

Neil Peart had little interest in the Rock formulas, setting the band apart from their peers

✎ WAYNE K. SPEAR | JANUARY 11, 2020 • Obituaries

IN THE EARLY 70s John Rutsey started a band with school mate Alex Zivojinovich. Their lead singer and bass player, Jeff Jones, left the band and soon after John left too. Jeff was replaced by Gary Weinrib, who took the name Geddy Lee, and Rush acquired a drummer by the name of Neil Peart. You know the rest.

My introduction to Rush was 1980’s Permanent Waves. This exciting new band had seven albums and a couple minor hits to their credit, but it was the songs The Spirit of Radio and Freewill that delivered fortune and fame. The songs sounded like nothing else we were hearing in 1980, a remarkable fact, because there was a lot going on then. Ska, Post-punk, New Wave, Reggae, and Disco were flourishing, but even among their progressive and hard rock peers, Rush were distinct. Hugh Syme’s grainy, post-apocalyptic, and artsy cover was an instance of form following content, perfectly capturing the spirit of a band that took its music seriously without taking themselves seriously.

Neil Peart wasn’t merely a drummer, he was a reader and a writer with a melodic approach to percussion. Neither Geddy Lee or Alex Lifeson had a knack for words, although Lee had been forced into the role of lyricist when John Rutsey tore up his sheets for the first Rush album. Peart’s imaginative lyrics recalled bands like Genesis and Led Zeppelin, grounded as they were in obscure myth and philosophy. At bottom they conveyed the struggle of the individual against conformity and compromise. Peart had little interest in the Rock formulas, which set the band apart in a manner satirized by the Trailer Park Boys character, Ricky:

Helix was a wicked concert. They had good lyrics. “Give me an R O C K,” and the crowd yells Rock really loud. Rush’s don’t do stuff like that. They got these lyrics about how trees are talking to each other, how different sides of your brain works, outer space bullshit.

Peart’s lyrics in other words weren’t for everyone, but in the 1980s and 1990s Rush produced a stream of albums capturing the restlessness of life in the 905 suburbs and celebrating the interior world of those who neither fit in nor wanted to. Along the way he penned nostalgic songs like Lakeside Park, a tribute to the St. Catharines waterfront where he had spent his youth. As a Brock University student I spent a good amount of time there myself. Rush was Canadian in a way and to a degree that others, such as Neil Young, are not, and to appreciate their music it probably helps to be from a certain time and place. This is not to deny their worldwide appeal, only to point out the fact that they remained rooted in their origins.

Neil Peart yielded an army of air drummers, and at one time or another many of us were the Jason Segel character from Freaks and Geeks, playing along to Tom Sawyer in our parents’ basement. John Bonham’s performance on Kashmir is the only worthy rival.

Rush’s Moving Pictures tour, which arrived at Buffalo Memorial Auditorium on May 9, 1981, was my second, or maybe third, stadium show. (Don’t ask me to recall the details: there were a lot of substances at a rock show back then.) The show was memorable not only for the skill of the performance, but because Peart lost the beat during The Spirit of Radio and threw off the band. The audience, and for that matter the band, had a good laugh. That was something audiences weren’t likely ever to see.

Rush would release fifteen studio albums and perform into the middle of the 2010s, when the physical stresses of performance would force Peart into retirement. In interviews Neil Peart was shy and retiring, as well as unassuming, and in life he was private. No one knew how seriously ill he had become. As Matt Gurney notes in an obituary, “Peart liked to slip out of his concerts without drawing any attention so he could ride off on his own, finding his centre again. It’s no surprise he chose to exit this life the same way.” ⌾

Gord Downie established himself as a symbol of Canada

Gord Downie established himself as a symbol of Canada Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 1977. His “Flying V” guitar is featured in the band’s logo.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 1977. His “Flying V” guitar is featured in the band’s logo.

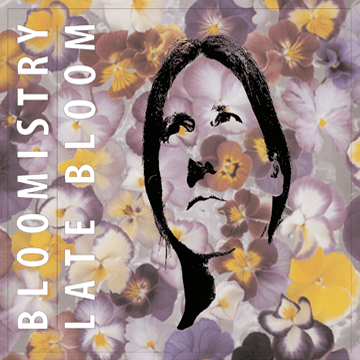

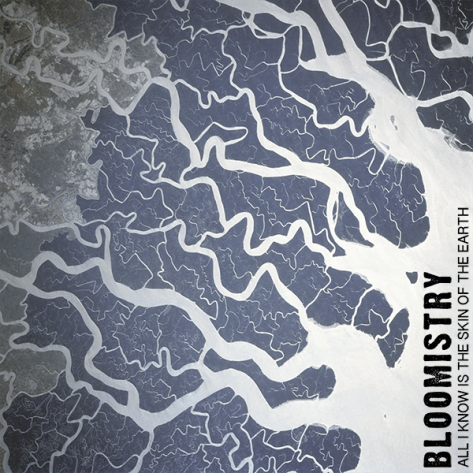

2007–2008 was an incredibly productive musical year for me. Recorded over three days (August 17–19, 2007), All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth was the 4th full-length Bloomistry album, following Late Bloom by only a few months. By the fall of 2008, a fifth album—At the End of a Difficult Day—would be finished.

Late Bloom was an album about returning to recording and live performance at age 40, after a long hiatus. All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth is a line from a Pablo Neruda poem. The working title, A City Like Me, reflected a growing desire to find a new place to call home. I was getting sick of Ottawa. Also, most of the songs for this album were written in hotel rooms, as was the case with Ca Marche and Late Bloom, adding to the album’s overall feel of restlessness.

All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth was made in a weekend marathon session and recorded to eight-track tape. That’s the best way to do it, in my opinion. The most focused and ambitious of my first four Bloomistry albums, it was self-consciously retro, featuring 60s instruments including most notably the combo organ. I imagined myself playing the soundtrack to a hip movie in 1962, kind of like Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Phil Bova mixed and mastered the record at Bova Sound, in Ottawa, on March 24–25, 2008. This remaster builds on this earlier version.

The album began as a series of stories told by characters (the pirate of “Sand and Sea,” the Casanova of “Bitter Sense of Melody” and the eponymous Undertaker) and in some cases real people that I knew. “On the Western Trail” tells the true story of an acquaintance of mine who was taken to Spain—kidnapped I would say—by the country’s poet laureate. “Higher Cloud” rehearses the sad story of Harold Funk, an attorney who suffered from mental illness and became a local legend by putting conspiratorial leaflets on the car windshields of Ottawa. There is an actual recording of Funk shouting at the US Embassy that I made on my walk to work one day and mixed into the song’s bridge.

All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth came closest to perfecting the post-punk, 60s-pop blend that was my aspiration. The next album would explore Americana, turning to lap steel guitars, banjo, Les Pauls and 50s amps and instruments. I regard this album as my best work. It was massive fun to make, and when it was done I had the best sushi dinner ever, at Wasabi in Ottawa.

Tracks.

1. The Found Cause

2. Via Maria

3. Another Other Life

4. The All About A Girl

5. Winter’s Summer Song

6. On The Western Trail

7. Sand And Sea

8. Mosquito

9. Bitter Sense of Melody

10. A City Like Me

11. Higher Cloud

12. Beatrice

13. With The Violins

14. The Undertaker

2007–2008 was an incredibly productive musical year for me. Recorded over three days (August 17–19, 2007), All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth was the 4th full-length Bloomistry album, following Late Bloom by only a few months. By the fall of 2008, a fifth album—At the End of a Difficult Day—would be finished.

Late Bloom was an album about returning to recording and live performance at age 40, after a long hiatus. All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth is a line from a Pablo Neruda poem. The working title, A City Like Me, reflected a growing desire to find a new place to call home. I was getting sick of Ottawa. Also, most of the songs for this album were written in hotel rooms, as was the case with Ca Marche and Late Bloom, adding to the album’s overall feel of restlessness.

All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth was made in a weekend marathon session and recorded to eight-track tape. That’s the best way to do it, in my opinion. The most focused and ambitious of my first four Bloomistry albums, it was self-consciously retro, featuring 60s instruments including most notably the combo organ. I imagined myself playing the soundtrack to a hip movie in 1962, kind of like Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Phil Bova mixed and mastered the record at Bova Sound, in Ottawa, on March 24–25, 2008. This remaster builds on this earlier version.

The album began as a series of stories told by characters (the pirate of “Sand and Sea,” the Casanova of “Bitter Sense of Melody” and the eponymous Undertaker) and in some cases real people that I knew. “On the Western Trail” tells the true story of an acquaintance of mine who was taken to Spain—kidnapped I would say—by the country’s poet laureate. “Higher Cloud” rehearses the sad story of Harold Funk, an attorney who suffered from mental illness and became a local legend by putting conspiratorial leaflets on the car windshields of Ottawa. There is an actual recording of Funk shouting at the US Embassy that I made on my walk to work one day and mixed into the song’s bridge.

All I Know Is the Skin of the Earth came closest to perfecting the post-punk, 60s-pop blend that was my aspiration. The next album would explore Americana, turning to lap steel guitars, banjo, Les Pauls and 50s amps and instruments. I regard this album as my best work. It was massive fun to make, and when it was done I had the best sushi dinner ever, at Wasabi in Ottawa.

Tracks.

1. The Found Cause

2. Via Maria

3. Another Other Life

4. The All About A Girl

5. Winter’s Summer Song

6. On The Western Trail

7. Sand And Sea

8. Mosquito

9. Bitter Sense of Melody

10. A City Like Me

11. Higher Cloud

12. Beatrice

13. With The Violins

14. The Undertaker