A COUPLE WEEKS AGO, Zoe Todd posted a YouTube video inviting people to read from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 388-page executive summary. The video was conceived by Erica Violet Lee and co-organized by Zoe Todd and Joseph Murdoch-Flowers, and its inspiration came from Chelsea Vowel’s blog post “Reaction to the TRC: Not all opinions are equal or valid.” Ever good one, that.

You can read a CBC article about this project here.

As a result of these amazing folks, people are now posting their readings of the TRC summary on YouTube.

Chelsea’s post, which I recommend, was itself a response to Conrad Black’s National Post article “Canada’s treatment of aboriginals was shameful, but it was not genocide.”

Black took up a Utilitarian argument, heavily inflected by 19th-century tropes and by the White Man’s Burden—arguing that European civilization was such a gift to the natives that there’s no way you could call what Canada attempted genocide, even if you preface it with the qualifier cultural.

His point-of-view, that aboriginal people should be thankful for the gifts of human civilization, has a vocal following. Maybe not a majority following, but likely a sizeable minority. And since it’s a common enough position, it should be aired and not just dwell in the dirty cracks of CBC’s comment section.

I love a heated debate, and I’d be happy to undertake one in my (limited) spare time. But, OK, I’m coming down now from the soapbox. Lord Black is not the point of this post!

That National Post article has indirectly inspired a YouTube campaign, in which ordinary people—i.e. people who are not referred to in public as “Lord Such & Such”—are reading the very report that Black dismisses—without having read it! Seems to me like a decent turn.

But I had another idea, too. That’s the real reason I have written this post—to tell you about my idea.

It’s called 94ways. I’m not 100% settled on this name, but it’s the best I’ve come up with so far, in my opinion.

The idea is to create a website and the related social media where people can post simple, practical, actionable ideas related to each of the 94 recommendations of the TRC’s document Calls to Action. It could be an idea they are planning to do, or one they’ve already done. We could all brainstorm. We could trade experiences and stories. We could bring the report to life.

Nowadays you can even do things like organize a Meetup or host a Webinar. All of this could be part of the 94ways.com or 94campaign.com or 94toRestore.com or whatever it ends up being called.

All of this and more. The only limits are imagination, human will, and courage.

One final thought

Years ago I had a conversation with Georges Erasmus about RCAP—the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (Actually, we had a lot of conversations over the years about RCAP!)

Georges was reflecting on the 1996 final report. It had just come out, and he was looking forward to a holiday, after his intense traveling and media work around that extraordinary and unprecedented five-volume, 4,000-page work.

You see, he went straight from being National Chief of the AFN to being co-chair of the Royal Commission. Every time the man tried to take a holiday, someone would arm-twist him into another job. In fact, that’s what happened after RCAP. Phil Fontaine called and said, “Georges, you’ve got to come help create this Aboriginal Healing Foundation. If we don’t do it by April 1st, we’ll lose the $350 million.”

Georges said, “I’m not looking for a job, Phil!” But it was futile.

He spent the next 14 years at the AHF, and even today he is hard-at-work, building up a nation run by the Dene, for the Dene.

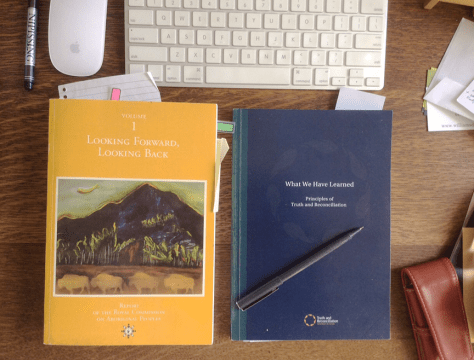

Anyway, what Georges told me was that, just as the report was to be distributed, the feds pulled the funding. As a result, RCAP lacked the resources it needed to properly and effectively get the report into the hands of Canadians.

Remember, this is before YouTube and Twitter and Facebook. It would be years before the technology existed to put RCAP on the Internet, and even more years before anyone did. (You can now find it here.) So back then, if you didn’t have an actual printed copy, you were pretty much out of luck.

And most of us did not have printed copies.

RCAP’s final report became a cliché: you know, the report that collects dust sitting on a shelf. Only I doubt it even did sit on a shelf in more than a couple Parliamentary offices. There were some great efforts to get the word out, for example by reading the entire report, page-by-page, on the radio.

A few lucky people (like me) managed to get the report on CD, but back then the technology was so primitive that they may as well not have bothered. It was designed for installation on a server running Windows NT, because back then a five-volume report was basically an unimaginably huge amount of data—certainly not something you’d pop into your lousy desktop.

I never did get that darn RCAP CD-ROM to work!

I’m sure the feds were happy to have a report no one could access. Because that meant no one could challenge the government to do something.

Well, it’s now 2015, and the people can do all sort of things. It will be 100% impossible for Mr. Harper and his kind to bury the TRC report, the way RCAP was buried, although they will try as best they can.

And they will fail.

Contact me if you think 94ways is a good idea.

Update (06/25): I have registered the domain 94ways.com and am gradually building the site. You can now visit and have a look around. The next step is to create the social media accounts. I hope to have this done in the coming days. Please share your comments, ideas, suggestions or other content here, or at 94ways.com. Thanks!